While moving piles of magazines around, I found this copy of Design Review, which was produced by the team that made Blueprint back in the early 1990s, when it was published by Wordsearch. It was an exercise in “contract”, the publishing company was paid by the Chartered Society of Designers (CSD) to create this quarterly magazine for its membership. I’m posting this article as a companion piece to “Mysterious Absence at the Cutting Edge”, which I wrote for Eye, as a member of the editorial team when employed at Wordsearch from August 1990 to August 1994.

First a disclaimer, this feature article was not primarily about the glass ceiling, the invisible barrier to promotion within a profession. More accurately, it is about inequality, discrimination and access across the design profession and education; I did not write the title or standfirst, which is common practice in journalism. And, yes, this is ancient history, written in my “cub reporter” days, but I think it is worth adding to the digital universe (I don’t think Design Review has been digitised or is likely to be). As at Blueprint, my editorial role at DR included pitching ideas for articles and writing, and as long as I was able to convince the editor and justify my choices and opinions I was able to write on a range of topics that interested me. This feature article was prompted by a seminar I attended at the CSD’s London Headquarters, and was probably anticipated as a promotional piece informing the membership about a recent event. However, I used the opportunity to interview women working in design who I knew had something to say: Jane Priestman, Penny Sparke, Jane Dillon, Anne Gardener and Siobhan Keaney. I remember that the research took time, as I travelled to chat in person and followed up with phone interviews (this was years before email), expending much more effort than I was expected to put into an article of this length. Somewhere, in a notebook, there are extensive notes and transcribed interviews and I hope to revisit these interviews at a later date. Reading the article again, it’s shocking to realise that the design disciplines at the Royal College of Art (RCA) were so gender defined, which was my experience of the college, as I had graduated just four years earlier. Consequently, when the separate disciplines of Furniture Design and Industrial Design were combined into one course, Design Products, the gender imbalance was redressed at a stroke, and it would be interesting to consider the affect of that move in more depth.

Another reason for highlighting this historical moment is to dispel the idea that Feminism comes in “waves” and that after the ideological tsunami that was Second Wave Feminism there were years of drought and doubt. I’ve lectured about how media representations of Feminism enforce this idea, that Feminism comes and and then goes, mirroring the wider political zeitgeist, and that in the 1980s and 1990s, Thatcher-induced conservatism quashed women’s resistance to inequality. In actual fact, that just isn’t the case; I came of age as a Feminist in the 1980s and will always claim the label.

More recent publishing activity has seen women in design raising profiles, telling their stories and stepping into the limelight as role models, with the publication of The Journey Is The Treasure by The W Project (an initiative by Teo Connor and Loren Platt), released on International Women’s Day 2013, to which I contributed an Introduction. And just last year, curator and design historian, Libby Sellers, published her compendium of women working in design through the 20th century to today, Women Design, published by Frances Lincoln, 2018. In an interview with Domus, Sellers explains: “Each of the entries takes on a different agenda – some look at the on-going issue of acknowledgement within a partnership, another focuses on issues of race, some highlight how larger political concerns have impacted on design, while all celebrate the talents and achievements of the designers”.

When re-reading this article from 1993 with regards to modernism, we should take into account new scholarship, by Seller’s and others, that has brought to light the role of women in the development of the aesthetic and the movement. Robin Schuldenfrei’s book, Luxury and Modernism: Architecture and the Object in Germany 1900-1933, published by Princeton University Press, 2018, highlights the domestic and luxurious aspects of modernism, expanding the aesthetic beyond the masculine and monumental and going some way to regendering the movement. So, the work of resisting patriarchy is continual, and it is useful to look back to see where we’ve come from, while celebrating the growing numbers of women entering every branch of the design industry. The glass ceiling is being chipped away at, while the ring fence has well and truly been trampled.

“The glass ceiling”

by Liz Farrelly

Design Review: The Journal of the Chartered Society of Designers

Issue 9 Volume 3 1993, pp.56-61

Cover illustration by Karen Caldicott

Standfirst: Why is the design profession dominated by men? And does it really matter? Liz Farrelly asked five women designers about their careers and the part they believe women should play in design. Photographs by Simon Horton.

Designers usually like to think of themselves as one of the more reconstructed professions, but just how equal are the opportunities for women in the industry? Take a look at the statistics. A recent Women in Marketing and Design seminar at the Chartered Society of Designers about women working in product design revealed that only twelve per cent of CSD product designer Members and five per cent of Fellows were female. Back in 1989, a Design Innovation Group study found that fewer than one per cent of the UK’s practicing product designers were women.

Of course, there are areas in which women dominate – at the Royal College of Art almost all textiles students and about half the graphic designers are female – but there are no women in the first years of the industrial design, industrial design engineering or vehicle design courses and only three in the second year. It appears that a form of design apartheid is being practiced, with areas prescribed as either “women’s work” or “men only”.

In a sense the design world mirrors the situation in society as a whole. According to Director magazine, only four per cent of company directors are women, virtually none of them holding functional executive roles. Women are being discriminated against and excluded from both educational advantages and the top jobs. The “glass ceiling”, the invisible barrier between women and promotion, is no myth.

But why should we worry if design is a male-dominated profession? Imagine living in a society where all the “professionals” were men and there were no female doctors, solicitors, police officers, nurses or teachers. What a waste of human resources! A vast group, not even a minority, would be subject to services, laws and education designated for them, without first-hand input from those on the receiving end. In the design profession that scenario is a reality, and it means that those responsible for creating objects and interfaces may not know enough about the needs of the user to produce designs which are genuinely helpful, innovative and efficient. Aside from being unjust, the imbalance is a serious problem. After all, the female “minority” accounts for the largest proportion of the design audience.

I asked five women working in design, in different roles and disciplines – furniture, graphics and industrial design, higher education and design management – and at various stages in their careers, to air their opinions.

They all have two things in common: all claimed initially that they were “too busy” to notice discrimination; and all have, at one time or another, been the only woman in a business meeting. Living in a patriarchal society may not mean women are discriminated against per se, but because male ways of thinking and acting are considered the norm, women constantly have to adapt and compromise. They deal almost exclusively with male clients, although a client’s office is invariably run by – and its decision-making is informed by – female support staff.

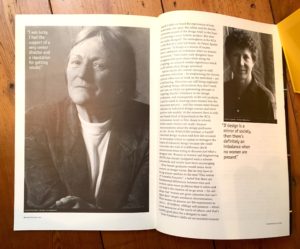

Jane Priestman has managed design and architecture at director level at the British Airports Authority and, more recently, British Rail. She retired in 1991 and now acts as a consultant to industry, both at home and abroad. She says she would be highly suspicious of any organisation where women were not equally represented, and thinks that men feel more threatened by women in organisational and managerial roles than in less senior, creative positions. She experienced difficulty gaining the trust of her male superiors and employees, but adds: “I was lucky. I had the support of a very senior director, and I had a reputation for getting results.”

All five women stress that to succeed at a career you need dedication, but that women are likely to be less one-track minded because of other priorities outside work – homes, partners, and children impinge on time and mobility. Men are more able to compartmentalise their professional and private lives. A recent report by the Industrial Society [renamed The Work Foundation in 2002] named pregnancy and childcare as the major causes of women not climbing the career ladder.

Jane Priestman laments the jobs she had to turn down because of familial duties. Jane Dillon has experienced similar difficulties. She graduated from the Royal College of Art in the late 1960s and went to work for Ettore Sottsass in Italy. She has worked as an independent furniture and lighting designer, initially in partnership with her husband Charles Dillon, for international companies including Barcelona-based Casas since well before the end of the Franco era. Dillon says: “My career isn’t where it should be. I need a clear run at an idea, lots of uninterrupted time to think, and you don’t get that if you have children.” This is a common problem for working women, but there are factors peculiar to design which seem to exacerbate inequality.

In this sense Penny Sparke’s work is enlightening. She is a design historian and theorist who lectures at the Royal College of Art and has published many books on the cultural and social ramifications of design. Her investigations into modernism, the dominant creed of design for the best part of the twentieth century, have identified how discrimination became “institutionalised”. Colleges, museums and government-run councils established by pre-war modernist crusaders embodied an ideology which rejected everything identifiable with women and their permitted roles in society – domesticity, decoration, comfort, hand work, display and consumption. Conversely, the values lauded by modernist designers – rationalism, technology, monumentality and mass-production – were unmistakably masculine. The result was cultural alienation and physical exclusion.

In our so-called post-modern world things are supposed to be different. Cultural pluralism is now the preferred stance, design students are urged to take on board the experiences of non-westerners, the aged, the infirm and the female consumer as part of the design brief, in the hope of achieving a more holistic product. But what has really changed? The atmosphere at the RCA is still that of a male hot house. As Penny Sparke points out: “If design is a mirror of society, there’s definitely an imbalance when no women are present.” How many male designers have struggled with pushchairs while doing the shopping, or endured similar experiences that could inform their design priorities?

Sparke thinks the current attempts to shift modernist orthodoxy – by emphasizing the diverse cultural influences at work on the individual – are a red herring. Minorities are still being neglected and end up being sold products they don’t want, can’t use, or which are patronizing attempts at targeting. Gender imbalance in the design profession, and consequently in the end products, could be cured by drawing more women into the discussion process – and that means more female students on industrial design courses and more positive role models. At the moment there is only one female head of department at the RCA. Information needs to filter down to schools, before career choices are made, because misconceptions about the design profession are rife. At the WMD/CSD seminar, a Cardiff industrial design student told how she revisited her secondary school to explain to teenagers the basics of industrial design because she could remember the wall of indifference she’d encountered when trying to discover just what a designer did. Women in Science and Engineering (WISE) has already instigated such a scheme nationwide and results have been encouraging.

More female graduates would mean more women on design teams. But do they have to bring unique qualities to the mix? This notion of “essential femininity”, a belief that there are fundamental differences between men and women raises more problems than it solves and can lead to the creation of no-go areas – the old adage that “women are great colourists but can’t space-plan” simply reinforces discrimination. What women do possess are life-experiences as carers – of children, siblings and parents – which create awareness of the needs of others, and that’s a pretty good place for a designer to start.

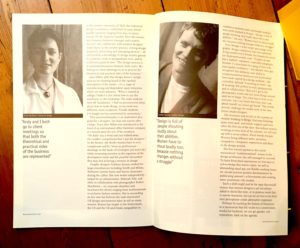

Anne Gardener’s skills are an essential element in the creative chemistry at TKO, the industrial design consultancy established in 1990 which handles projects ranging from toys to trains, mainly for the Japanese market. Her role crosses over between business manager and creative theorist. She collaborates with product designer Andy Davey in the creative process, writing design proposals, presenting and managing projects – all informed by a knowledge of design history gained by academic study at postgraduate level, and by a different point of view: “The design process is a continual discussion between Andy and I. We both go to client meetings so as to present the theoretical and practical sides of the business.”

Jane Dillon adds that design doesn’t simply exist on the drawing board in the rarefied atmosphere of the studio – it’s a stage of manufacturing and dependent upon industries that are male domains. “When I started at college I hadn’t a clue about how to use the machinery in the workshop. The male students were all ‘handymen’. I had no preconceived ideas about how to make things, so my work was different, more sculptural. Female students I’ve taught are less constricted by convention.”

This unconventionality is an undoubted plus point for a designer, but may not survive after college. Years later Dillon was introduced to the head of an international office furniture company at a launch party for one of her products. “He didn’t say a word and just walked away. He couldn’t comprehend that I was the designer.” In the factory, she thinks women have to over-compensate and be “twice as professional – drawings on the backs of envelopes just won’t do,” while also remaining sensitive to the expertise of the development team and the possible discomfort they may feel at having a woman in charge.

Graphic designer Siobhan Keaney worked for large consultancies including Smith and Milton, Robinson Lambie-Nairn and Davies Associates during the 1980s. She now works independently – helped by an administrator, Deborah Tilly, and often in collaboration with photographer Robert Shackleton – on corporate identities and brochures for clients ranging from multinationals to exclusive fashion retailers. She is succeeding on her own but believes the male-dominated UK design environment takes its toll on many women. Keaney has taught in the Netherlands, the US and the UK and thinks inequalities in confidence between male and female students were most marked in Britain. “Design is full of people shouting very loudly about their own abilities,” she says. “Women have to shout loudly too, because nothing changes without a struggle.”

Even though a much larger percentage of the graphic design community than the industrial design profession is female, the household names are disproportionately male. “Graphic design has a ‘laddish’ reputation, especially typography, because it’s dominated by a gang of men with train-spotter tendencies,” says Keaney, who also recognises that distinctly male ability to compartmentalise emotional and professional lives is made explicit in a design aesthetic – the controlled, defined, “everything in boxes” way of working. She prefers to work spontaneously and in collaboration: “Rob and I get in the photography studio and just move things around until we’re happy. The client has to trust to the outcome, but I can foster that trust, and I can please myself, so I never get bored.” The results directly challenge the media myth of the lone, heroic (male) designer.

The recession took its toll on the number of women working in design. Part-time lecturing posts were axed, and female support staff were often the first out the door. But without women working at every level of the industry, we will end up with a mono-culture, which breeds myopia. Women bring different tastes, priorities, sympathies, viewpoints, experiences and ideas to the design process.

The five women quoted in this article encountered “institutionalised” sexism in the design profession, but still managed to succeed. To learn from their experiences we first have to acknowledge that sexism exists. As well as demanding equal pay and flexible working hours, we should practice positive discrimination by publicising women’s achievements and creating more prominent role models.

Such a shift might just be the spur that would ensure that women designers are not always asked to think like men, or to produce work that is overtly feminine, but can be set free to let their own perceptions create alternative responses.

Perhaps by teaching the history of feminism as a movement that fell victim to a conservative media-led backlash, we can get gender, not separatism, back on the agenda.