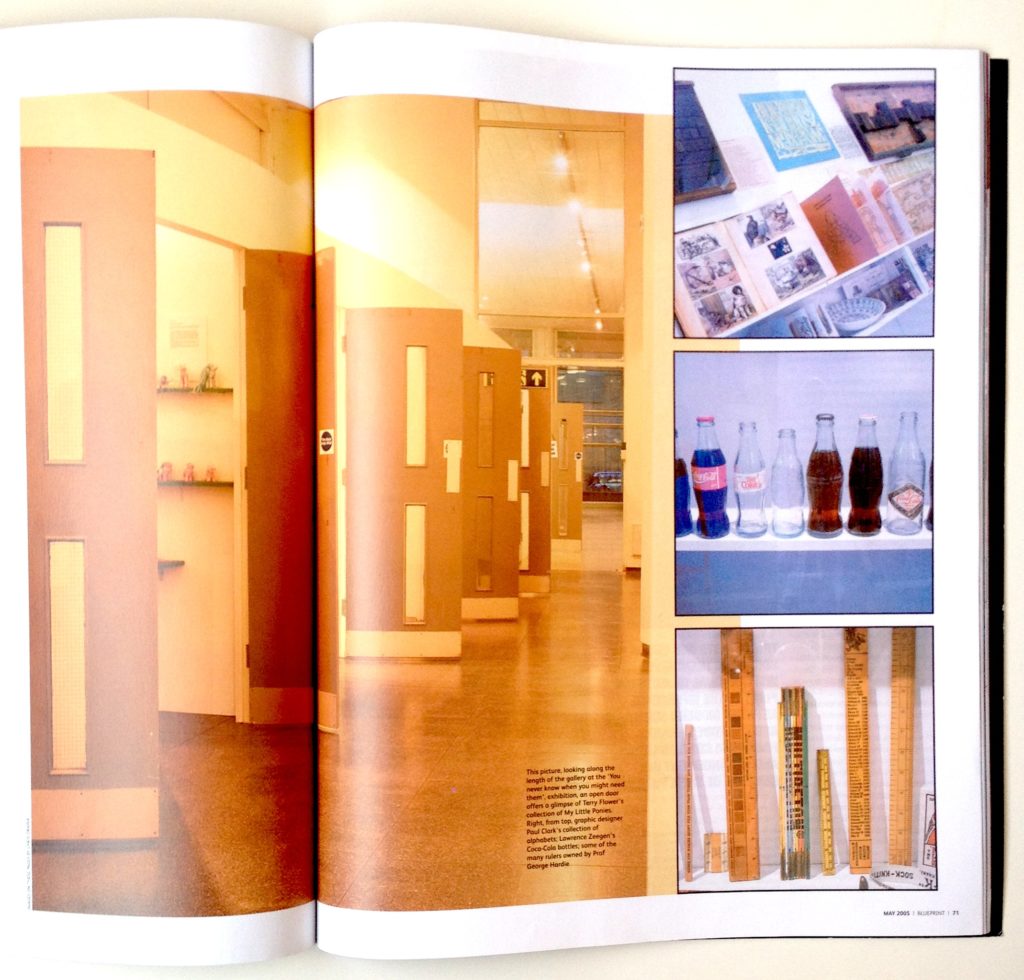

Spread from ‘Blueprint’ showing the University Gallery in Brighton and the exhibition design featuring salvaged fire doors

I was reminded of this article when visiting another exhibition, George Hardie …Fifty Odd Years, also at the University Gallery at University of Brighton. (Look out for a review of that exhibition, soon).

Back in 2005, Professor Hardie contributed his collection of rulers to You never know when you might need them, and they feature in the opening spread of the Blueprint article about the show, see above. At the time, my husband, Gregg Virostek, was an Interior Architecture student and worked on the exhibition build, while I was beginning to explore an obsession with collecting. That interest has developed into a research topic, as evidenced by this blog. So, as this article has yet to be digitised and made available online by the originally publisher it, here it is for reference.

I’ve left the article as it was published, apart from correcting the name of the University (!) but would like to preface it by addressing two stand-out comments. Terry Meade batted away grumbles that the exhibition ‘wasn’t “curated”’ by pointing to the flexibility of the installation, which was able to absorb last minute contributions during the build. That open-ended, down-to-the-wire flexibility allowed a wider community to engage with the project, inspired by the sight/site of the exhibition as a work-in-progress. Later in the article, Chris Draper asserted that museums are too organised, meaning over-curated, whereas collecting allows for engagement with objects through handling and re-arranging. That made me think again about the concept of the Schaudepot (see, here), which to an extent addresses this issue. We aren’t actually invited to pull up a chair, but the informal/minimal presentation enables multiple viewpoints that allow for a more personal ‘seeing’ of objects and encourages unexpected juxtapositions. Mobile/Smart technology adds interpretation, via hand-held devices or later at a distance, and again, the choice is yours. Both these comments, from Terry and Chris, made me think about how museums might facilitate more flexible and personal engagement with objects, by way of displays that remain open to change and ‘within reach’.

Meanwhile, the idea of the artist’s collection as inspiration was further explored in the exhibition, Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector, at the Barbican Art Gallery. I hate to admit that I missed it, but if it tours, I’m there!

‘Creative Collecting’

by Liz Farrelly

Blueprint, No.230, May 2005, pp.70-73

Standfirst: Coke bottles, toys, defunct electrical devices…all manner of discarded objects make up the personal collections of designers. Liz Farrelly explains why accumulation is an important part of the creative process

For more than a decade museum curators and museologists have been asking, how do we collect and why? While the rhyme and reason for creative individuals amassing collections, which for many are crucial to their practice, has remained a mystery, a recent exhibition asked some penetrating questions. Why is it that one person’s inspiration may look like a bunch of old junk to the rest of us, and how is it that artists and designers interact with their very personal selection of objects? And, do they collect in a particular way that affects the process of creativity?

A curving, white structure stretched the length of University of Brighton’s gallery at Grand Parade, home to the institution’s art school. Eighteen fire doors were placed at intervals along the anonymous façade. Still in their original state, painted gunmetal grey and complete with official signage, the doors came from a skip outside a refurbished nursing home. If you had passed through any of the doors you would have entered a maze of small spaces housing alcoves, shelves, and cabinets. Within these were the flotsam and jetsam of more than 30 collections contributed by artists, designers, film-makers, lecturers, writers, and historians, all linked in some way to the University. Titled You never know when you might need them… the exhibition, held in January, showed collections of objects that have been inspirational to their owners’ creative practice.

Contributors had donated all manner of stuff; from every type of plastic coffee stirrer to rusting artillery shells, from defunct electrical testing devices to a whole livery stable of My Little Ponies, from Coca-Cola bottles to a pair of 19th-century men’s linen trousers. Other collections feature playing cards found on the street, Eastern European hosier packaging, alarm clocks, rulers, alphabets, arrowheads, dead relatives’ wallets, plastic bullets from the Maze prison in Northern Ireland…

On the street side of the gallery, floor-to-ceiling windows offered oblique glimpses of the eclectic mix of goodies. With prime-time television hunting down ‘collectables’ and quizzing proud owners, in programmes such as Flog It and Bargain Hunt, it’s official – we’re all fascinated with other people’s stuff. No wonder the exhibition pulled in the crowds, proving to be the most popular ever to be staged at the University.

In the gallery, exhibits were hidden from view; visitors chose to enter a room, alone or with others. They moved through a succession of intimate spaces in any order, so that each viewer personalised their experience of the show. The upshot of this freedom was that the juxtaposition of objects and the flow of the exhibition were entirely random; perhaps you would find ‘a chance encounter between a sewing machine and an umbrella on an ironing-board in an operating theatre’. [Misquote, not sure where the ironing-board came from! Should read: ‘the chance meeting on a dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella!’ from Les Chants de Maldoror (1869) by Comte de Lautréamont AKA Isidore Ducasse (1846-70).]

Rescuer of the doors, curator and exhibition designer, was architect Terry Meade, [then] subject leader in Interior Architecture at the University. Asked about the motivation for the show, Meade recalls: ‘I’ve always been interested in artists’ studios, the images and objects that artists collect around themselves.’ His own practice involves a process of collage. ‘I collect images found in newspapers and magazines, at the dentist, on planes,’ explains Meade. His archive exists in piles of boxes, stuck into sketchbooks and, more recently, as digital scans. ‘Part of my design process is to move those fragments about, juxtapose and layer them, draw over pages in old sketchbooks, and build up an idea of space from a chance collection of bits and pieces,’ he says. Some of Meade’s collection, images of walls (from Berlin to Bethlehem), was include in the exhibition.

‘I’ve always been interested in what other people collect, and the initial idea was to include a piece of each contributor’s work in parallel with their collection, which would be, in effect, the raw material. But I had very little idea of what was going to turn up,’ he says. Chance took over, and as Meade and his team of students were busy finishing the structure, contributors arrived, claimed a space and unpacked their treasures.

‘We built a calm exterior to hide the dense inner space where collections could be placed up against each other. The door idea came first, inspired by Home Show I (an exhibition in 1988), where all the doors in a house were removed and piled in the living room, to reveal the usually hidden belongings,’ explains Meade. ‘There were some comments that the show wasn’t “curated”, but we had a loose plan, moving from domestic objects to weird stuff to political memorabilia. And we were able to absorb more and more as volunteers came into the gallery during the build to offer their collections.’

How contributors behaved around their stuff provided more research material, explains Meade. ‘It looked like organized chaos, but each collector was very particular about how they arrange their objects. Building a world around yourself with your belongings is one aspect of collecting. Recalling by association events and memories, often from childhood, is another; so is ‘the chase’, noticing objects on the street or tracking down rare examples; all of these realities were mentioned in the contributors’ written statements.’

The exhibition may have grown out of a random selection process, but eventually it came to represent different ways of collecting. There are those collectors who focus on amassing every example of one particular object or type of object. Illustrator, Lawrence Zeegen ([then] programme leader in Communication and Media at University of Brighton) represents the classic collector, much studied by museologists and interpreters of material culture.

‘The Coke bottle collection started when I was a student. They’re cheap and easy-to-find design classics; it just snowballed from there. I see one, then I need it! I travel a lot and can’t rest until I have a particular one. The bottle has to be full and different. People also bring them back from their travels for me, and I’m always saddened if they’re empty. I buy on eBay, but only if I have to!’

In her essay, ‘Collecting Reconsidered’, museologist Susan M. Pearce identifies three types of objects and collections. One, the souvenir, is intensely personal or ‘curious’, and may be described as that amassed by an individual during their lifetime, often to be donated to a museum. Two, systematic, by which objects represent ‘principles of organisation’ that are scientifically verified via observation and study, the classic, one-of-every-kind approach. And three, fetishistic, meaning objects which are ‘artful’ or ‘magically active’, collected by ‘people whose imaginations identify with the objects which they desire to gather’.

Meade’s aim of showing collected objects that are crucial to creative practice appears to have paid off, as most of the objects/collections fit naturally into this final category. Admittedly, in some collections there was crossover between categories, but in general it was the ‘non-creative’ collections that are all about having no two alike, be it butterflies, coins, stamps or Coca-Cola bottles.

Pop culture aficionado Zeegen has another collection too, ‘…of Clip Art, which is integrated into my way of working’. Large office-type ring binders of sheets of photocopied ‘art’ constitutes the collection. ‘It’s what I’m most interested in, because I love design that has been created by non-designers,’ explains Zeegen. ‘I educate designers and illustrators, but crave the work of those not influenced by people like me. Clip Art is honest design, for the people, because it communicates. I’ve also taught myself to draw images that look like I found them.’

An exhibitor who has made the study of collections part of his practice as an Illustrator is Chris Draper ([then]visiting lecturer at University of Brighton). ‘The museum is “the muse’s resting place”,’ Draper says. ‘You’re at your most creative in an environment that you feel comfortable and inspired in. Whether you surround yourself with tin toys or religious icons, that’s a matter of taste. Your choices can make other people feel uncomfortable enough to stay out of your private, creative space.’

With a lifetime spent diving into skips, beach combing (including the Thames) and flea-market scavenging, Draper’s live/work space is crammed with objects arranged into cabinets of curiosities. Among his treasures are Neolithic tools, saintly relics, meteorites, medical models, and the teeth of a black rhino. ‘I started as an accumulator, then I spotted patterns, which turned me into a collector. I see very close links between designing and collecting: they’re both about imposing order on a chaotic world, and the more you have or know about an object type, the more complete the solution will be.’

When commissioned, Draper will build a temporary structure of objects, photograph it, and then return the components to their shelves. ‘Nothing is nailed down, the collection is very fluid. You need to handle objects to understand their physical nature, and rearrange them to make imaginative connections between things,’ he says. ‘That’s the problem with museums, their objects have been pre-sifted and are often over-curated, too organised. Making imaginative connections as a way of communicating is another function of design.’

Draper also uses historical forms of classification, defined by 16th and 17th-century scholars, as starting points for ordering his cabinets; a Wunderkammer being ‘a repository for extraordinary objects’, that is, natural, and a Kunstkammer, ‘a chamber for artistic objects’, that is, man-made. These Renaissance men felt the need to surround themselves with collections of objects in order to understand the causality of existence. It’s from their encyclopedic collections that the modern museum evolved; meanwhile in Italy that ‘dream space’ was named Studioli.

That artists and designers still surround themselves with inspirational objects may point to the difference between modern scientists (who rely on highly codified methods of experimentation to explore the world) and creative thinkers/makers, for whom conscious and unconscious contemplation and arranging of inspirational objects is a key part of their practice.

From Eduardo Paolozzi’s Crazy Cat Archive at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, to Andy Warhol’s weekly files of kitsch (from junk mail to bad art), housed in his eponymous museum in Pittsburgh, the objects artists and designers collect may provide an understanding of how they tick. Because, as we know from exhibitions like You never know when you might need them, other people’s stuff is really interesting.