Lucienne Day in New York with Calyx (1951), 1952: The Robin and Lucienne Day Foundation and archive. Photographer: Studio Briggs.

The current issue of Blueprint celebrates the life and work of Lucienne Day in the centenary year of her birth, with articles by and about her. The back pages of the magazine collect previous articles about the renowned designer, including a review I wrote about an exhibition at Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery, long before the stunning renovation and addition (mentioned in a previous post about Manchester, here); when I visited the Gallery presented a perfect example of late Victorian institutional architecture, a fine addition to the “Red Brick” University of Manchester. Initially, the thought of re-reading an article written over 24 years ago was a bit daunting, but then it helped me recall my first time in Manchester, an extraordinary day trip, meeting Lucienne Day and Jennifer Harris (the curator and author of the exhibition catalogue), and the privilege of walking the exhibition in their company. A new exhibition at the Gallery, Lucienne Day – A sense of growth, from 14 April to 11 June 2017, examines how plant forms inspired many of Lucienne Day’s iconic patterns. I hope to get back up north to visit it…

“British design’s first celebrity”

by Liz Farrelly

Blueprint, June 1993, pp.36-38

Exhibition review of Lucienne Day: a career in design

Whitworth Art Gallery, Oxford Road, Manchester

23 April to 26 June 1993

Visited 22 April 1993

Calyx screen-printed furnishing fabric, Lucienne Day, Heal’s Wholesale & Export, 1951: The Robin and Lucienne Day Foundation and archive.

After a long and distinguished carer, Lucienne Day is being honoured with a retrospective exhibition which, appropriately enough for a textile designer, is in Manchester. Over 80 per cent of her furnishing fabrics are here, supplemented by examples of designs for wallpaper and tableware, showing a great virtuosity of image-making and variety of aesthetics. And while the exhibition sheds light on an individual’s career, it acts just as effectively as a review of changing styles in domestic taste, albeit at the upper end of the market.

Over half a century, Lucienne Day has seen both the practice and the aim of design undergo monumental changes. Fifty years ago, the profession of design hardly existed. Its practitioners were for the most part anonymous, with an undefined status on the payroll of various manufacturing industries, and it was hardly a glamorous career. Most designers lived in factory town, worked nine to five, had no opportunity for visual research and could exercise little or no control over how their ideas were realised. The freelancer wasn’t much better off. In the textiles industry a pattern designer would produce a croquis, or motif sketch, get on a train to Manchester and do the rounds of the mills. If the design was bought, then an in-house team would work out the repeats and colour ways, and specify the quality of cloth to be used.

Lucienne Conradi graduated as a textile designer form the Royal College of Art in 1940. Her diploma show was designed by a friend, Robin Day, who soon became her husband. Uninterested in the novelty aspect of the fashion business, but having a love of architecture and modernism, she was drawn to furnishing textiles. Her particular desire was to dispel the gloom of war-time austerity and to design affordable, modern textiles for a younger generation who wanted alternatives to traditional florals and chintzes. Day gathered source material from avant-garde painting and sculpture. “We looked everywhere for inspiration,” she says, “and read all the international magazines.” She experimented with mark-making techniques, using cut paper, monoprinting and layering fine pen work over solid colours, to re-interpret natural and symbolic forms. Most of the original artwork has been lost, but three pieces have been rescued for the exhibition and are on show next to the finished cloth.

Black Leaf tea towel, Lucienne Day, Thomas Somerset & Co, 1959: The Robin and Lucienne Day Foundation and archive.

Being a pioneering modernist could have presented problems. “But I didn’t look like a bohemian, all beads and sandals,” says Day. “I loved clothes and spent so much money on looking smart that when I met the manufacturers they were quite relieved and happy to work with me.” Reluctant for her work to be tampered with, she presented completely worked-up designs. This also meant she could specify more adventurous, even daring, colourways, gaining added respect for the demonstration of technical expertise, and could charge twice the normal fee. She also made sure she checked the colour reproduction with the printer.

Lucienne Day’s career really took off during the Festival of Britain, even though she declined to join the Festival Pattern Group – “I didn’t need anyone telling me where to get my inspiration from”. [see Harriet Atkinson’s scholarly The Festival of Britain: A Land and Its People (2012) for an in-depth analysis of the event.] Robin Day was designing a room-set for the Homes and Gardens Pavilion but couldn’t find any suitable fabrics, so he suggested to Lucienne that she contribute a design. She approached Heal’s to print the fabric and, despite misgivings that it was too “modern” to sell, they went ahead. “Calyx” was a huge success, winning a Gold Medal at the Milan Triennale, and the coveted International Design Award of the American Institute of Decorators – the first time a British designer had received the honour. It sold in vast quantities at home and abroad. Without signing anything as formal as a contract, Day went on to produce annual collections for Heal’s – between four and six different designs in a host of colourways – for over twenty years.

Heal’s produced illustrated brochures featuring Day’s designs, and added the recommendation “by Lucienne Day” down the selvage of every roll. While she became a household name, Mr and Mrs Day became an early “designer couple”, photographed by advertisers and magazines in their modish Cheyne Walk home, and drafted in by the BBC to offer design advice to the nation.

With her already high profile turning international, Day became an unofficial, and much in demand, ambassador of British design. She was commissioned by the German wallpaper manufacturer Rasch to contribute to its Artists collection, along with the great and the good of European design, which brought her to the attention of Philip Rosenthal, the fine porcelain manufacturer. Twice yearly she would visit the factory in Bavaria to work with an international panel of designers, adding surface patterns to Raymond Loewy’s Service 2000 range and selecting products for Rosenthal’s Studio Houses.

Bond Street porcelain plates, pattern designed by Lucienne Day, Rosenthal, 1957: The Robin and Lucienne Day Foundation and archive.

While researching the exhibition, Day suggested to curator Jennifer Harris that she place an advertisement in the architectural press asking if owners of her textiles would become lenders, “because a lot of architects bought my fabrics”. Day’s aim as a modernist was to produce designs which worked within architectural spaces. “When I began a design I always thought of a particular room in my house and what it needed, because no one element in an interior should ever be more dominant than any other.” Her patterns grew in scale as she worked increasingly for architects, specifying for newly-built civic buildings in the 1960s and 1970s, looking for patterns that wouldn’t be lost in a school hall or council chamber.

The fact that architects appreciated Day’s designs might suggest that they were more avant-garde than popularist, but the volume of sales disputes the received belief that mass taste is always conservative. Besides, Day was in the right place at the right time. A new audience was crying out for glamour and quality, and the fact that her designs were copied and adapted as smaller sale patterns for smaller rooms, and printed on cheaper cloth, is further proof that mass taste was undergoing a transformation. Day herself could be accused of elitism, working only for expensive retailers. Yet a few designs for British Celanese, printed on an early acetate rayon at much lower cost, are now so fragile they have almost disintegrated with handling, proving that cheaper fabrics offered no saving in the long run. Eventually, it was new technology that emancipated her designs by reducing printing costs.

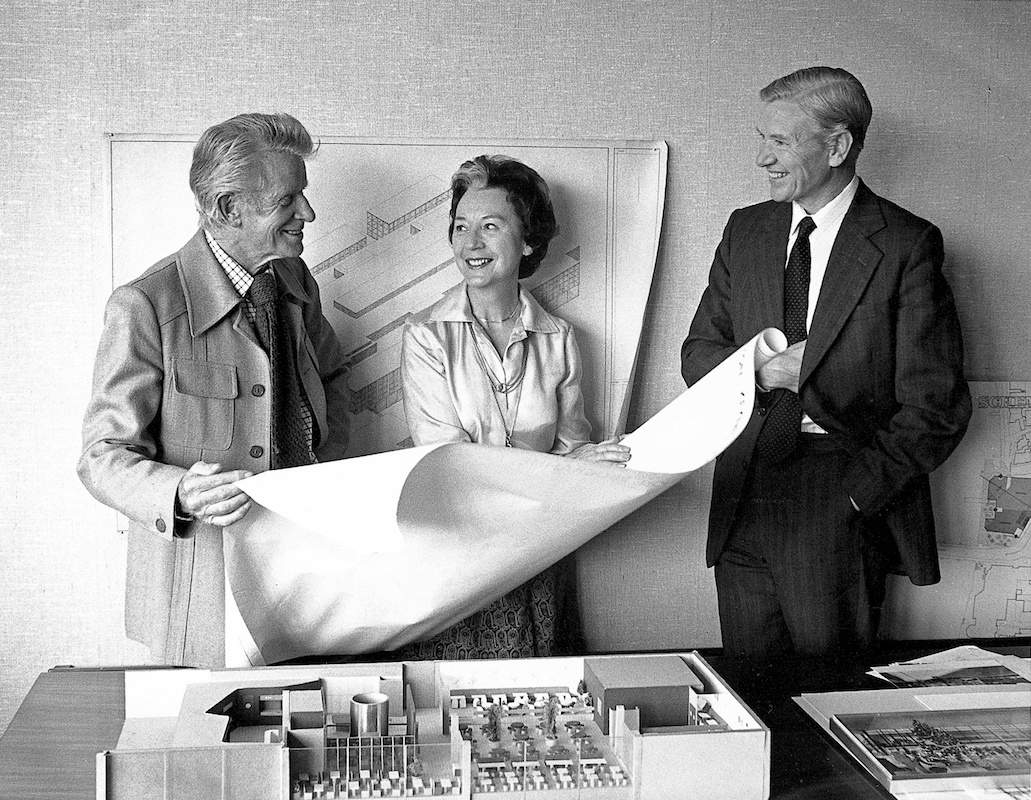

Robin and Lucienne Day with Harry Legg from John Lewis Partnership, 1979: The Robin and Lucienne Day Foundation and archive. Photographer: Trevor Fry.

By the mid-1970s, Lucienne Day felt she had contributed enough to industry. Sharing the role of design consultant to the John Lewis Partnership with her husband, she discovered a new image- and pattern-making technique which led her work in another direction. Commissioned to design a mural on roller shutters for a new store, the dimensions of the slats translated into a mosaic technique. Reinterpreting the mosaic theme in silk, Day created visual puzzles and pictures in subtle shades and textures, which have grown to the dimensions of wall-hangings and are regularly commissioned by architects.

Aspects of the Sun silk mosaic, Lucienne Day, 1990: The Robin and Lucienne Day Foundation and archive.

Lucienne Day is a designer who helped define the visual character of the home for over twenty years, and whose professionalism and perfectionism have led to major changes in the role and image of the designer in industry. This well researched celebration of her work is much appreciated and long overdue.