Screen Shot of the British Museum’s Libraries and Archives webpage, with information about the Central Archive.

Using Museum Archives

British Museum

Great Russell Street, London WC1

13 July 2015

The audience was welcomed by the event’s organisers, Laura Carter of University of Cambridge and Sarah Longair of the British Museum, who urged us to join the Museums and Galleries History Group and read Museum History Journal, both of which were new to me.

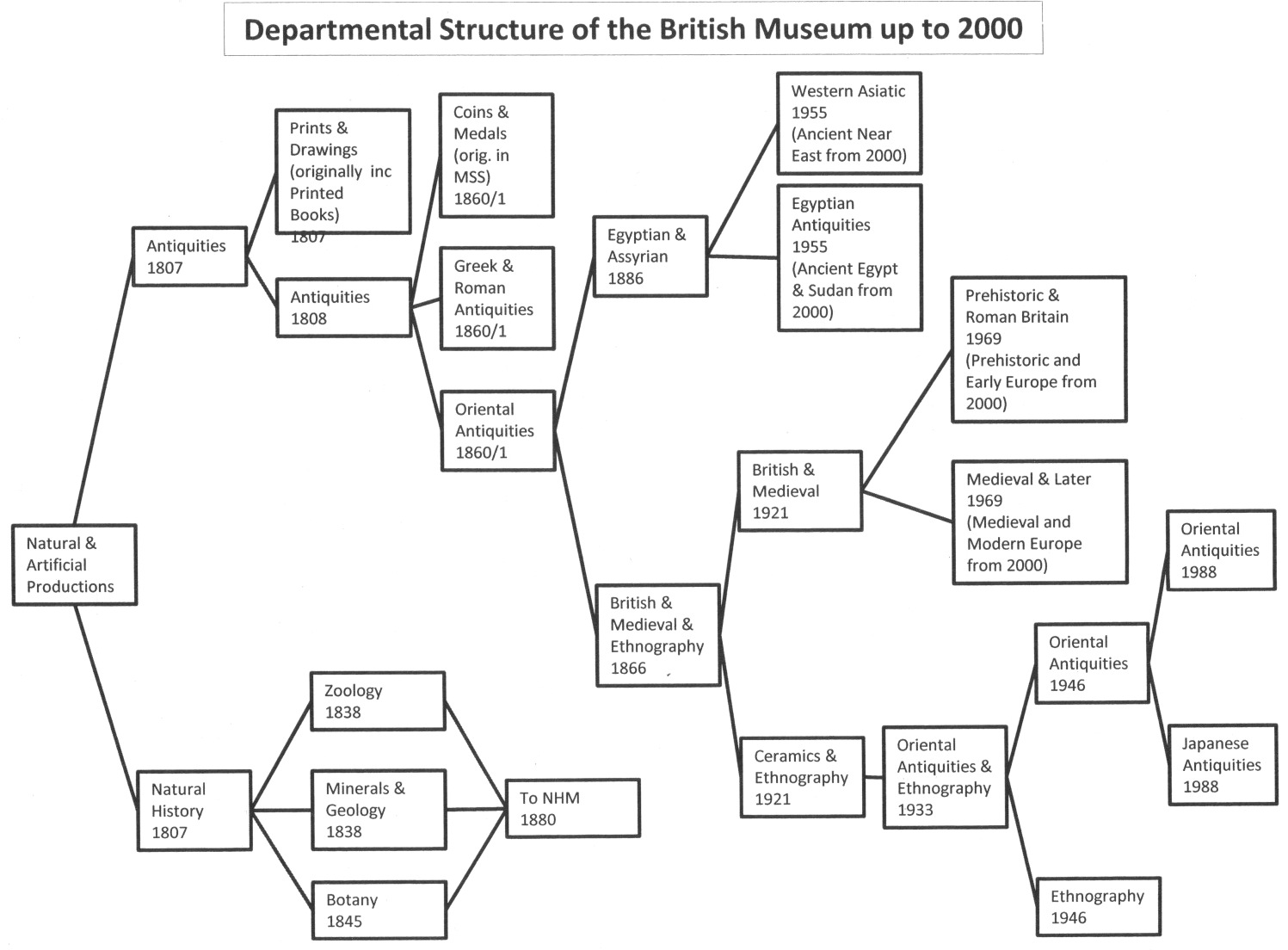

Francesca Hillier, Central Archivist at the British Museum, began her talk with what I consider a shocking fact, that she is the only archivist employed by the Museum, and went on to describe an institution built on eccentricities, which made me realise (again) that I’m as fascinated by the history of museums as by the objects within them. We heard that the Central Archive holds the deeds for the land and buildings of the British Museum; minutes from Trustees Meetings, since 1753; and internal reports and administrative records. Francesca emphasised the Museum’s “very complicated” history that has led to departments also having archives (perhaps due to their quasi-sovereign power despite name changes and reshuffles). For while Keepers were required to justify collecting activity to the Trustees, they also managed to “slip stuff in”, bought or acquired independently, which meant that record keeping was a hot potato. The hiving off of Museum departments into separate institutions – the Natural History Museum and British Library – has further complicated matters as archival material may have followed the objects, or not.

Francesca described the Museum’s online catalogue as “ad lib”, another shocker, particularly as the British Museum emphasises a commitment to digital delivery and data management (see the big data conference review, here). Other highlights of the Central Archive include the British Library Reading Room archive and a collection of gallery photographs. The Museum has employed a photographer since 1857 and the photographs are a unique record of the development of gallery displays. However, Francesca revealed that prior to her arrival the photographs weren’t considered archival material; and there is no information about which are originals or copies, or about copyright ownership. A “picky” approach is how she described early attitudes to documents, with untrained individuals “acting on the archive” to keep what they deemed worthy. And, while the Museum’s archives are “public records” financial constraints dictate accessibility; for instance, it is prohibitively expensive to digitise hundreds of microfilms so these can only be viewed in person, by appointment.

Chris Manias (King’s College London), billed as an historian of science and technology, is also interested in museums and collections and researches science on display via exhibitions. For his purposes “behind the scenes stuff” is easier to find and more useful than reconstructing the look of exhibitions or tracking down visitor reactions, as gallery photos were often idealised and staged. Conversely, schemata used for the planning of galleries are rare, but gallery maps that appeared in printed publications are more common. Another source is the Annual Report, which gives a blow by blow description of museum activity including gallery re-installations. This is interesting as regards my research into London’s Design Museum, which began life as the Boilerhouse Project in a gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Prior to the V&A becoming a Trustee Museum it did not publish Annual Reports, but there was an equivalent, the Victoria and Albert Museum Album published annually from 1982 to 1989. The Boilerhouse’s conspicuous absence from these publications underlines its status as a temporary, external alliance rather than a Museum gallery.

Other published and internal documents with historical pedigrees that Chris regularly consults are: “Intelligence Reports” of fact finding visits around the world, revealing a “curator’s eye view” of other museums; “Museum Guides”, the mediated view, how the museum presented itself at various historical moments; “Design Briefs and Gallery Management”, post WW2 instructions for the re-organisation of displays were recorded as museums became more bureaucratic, prior to that they were usually oral instructions; “Old Exhibition Material”, these actual display materials are rare and mostly uncatalogued. When Chris suggested “jigsawing” the various sources together, I realised that’s been my approach!

University of Cambridge AHRC CDA candidate, Rebecca Coll, is focusing on the work of Noble Frankland, Director of the Imperial War Museum (IWM) from 1960-1982, using the Museum’s archive and the Frankland archive. Rebecca had identified a number of problems with the “official record”; Frankland had “curated” his personal papers prior to donation; at the Museum, there was missing information due to a “lull” in administration after the Deputy Director resigned in 1979; and there was no documentation about the process or progress of planning exhibitions and displays – opening dates could be plotted and opinions about the end result are noted, but there is little evidence of how ideas evolved. Finally, there was a lack of emotion and individuality in the “official” version. To compensate, Rebecca instigated an oral history project with past employees, asking some standard questions and others tailored to particular roles so as to discover the “culture” of the IWM. As part of her process, Rebecca reviewed literature about oral history and interviewing elite subjects (I’ve also done this – museum personnel and, especially, Directors are “elite”). She also highlighted ethical issues relating to permissions, copyright, and “off the record” comments, admitting that it is difficult to “know but not include”. Her parting question was; “will these oral histories be accessioned into the archive?” …and I’m certain she wasn’t the only researcher in the room wondering that. Later, in the Q&A session Rebecca recalled that an interviewee didn’t want to go on record but she was able to verify the comments from an earlier interview found in the archive, which is in the public domain.

Caroline Cornish, from Royal Holloway University of London (RHUL), takes an object-based approach to her research; she suggested we look for the unexpected in the archive as “everything is a document…written upon and written about”, and reminded us that “a museum collection is an archive” too, because objects are data in physical form. Her research into “school museums”, housed in glazed cabinets and amassed after the 1870 Education Act introduced free elementary education in Britain, revealed a culture of “learning through seeing”. Intended to provoke curiosity these were collaborative endeavors with objects collected by pupils and teachers, informed by articles in Teachers Aid journal. In 1914 a head teacher suggested that “children remember well things they see and handle”; perhaps these ad-hoc collections, used in school rooms, could be considered as forerunners to today’s hands-on gallery teaching, which is central to museum education. (See, Museums and the Education Agenda by the Museums Association). Interestingly, Caroline commented that research into museums and education has received “negligible” coverage in academic literature; again that struck a cord with my own project.

During the lively Q&A session, a question about how archivists might help historians understand documents that were initially produced as internal communications prompted the observation from Francesca that contemporary minutes are less interesting; Trustees are circumspect, knowing their comments are public. (See the National Archives explanation of The Public Records System, here. In contrast, Human Resources records remain “locked”, making it difficult to verify dates of employment. Thomas Kiely from the British Museum, who spoke about “lost personnel”, mainly freelancers who worked with but not in the museum, suggested “putting those problems on record”. Caroline added that there are gaps in archives during sensitive periods; regime changes, sacking, scandals. Again, this is good to hear, as it verifies issues that I’ve encounters, so they are not unique to “my institution”. Amara Thornton of University College London (UCL), who spoke about ephemera, succinctly defined it as “minor transient documents of everyday life” (guidebooks not catalogues; paperwork in museum offices rather than archives) and suggested researchers make themselves aware of the framework within which (when and how) documents were produced. That could also include understanding the working practices of printers, publishers, writers, editors and designers and the production of printed matter. Design historians are well equipped to use material culture analysis as a route into the study of museums and archives.

After lunch and a document handling session, the keynote lecture was delivered by Kate Hill of University of Lincoln (Chair of the Museums and Galleries History Group and co-editor of Museums History Journal). Kate set out to tackle big issues; “culture and class” and Michel Foucault’s “knowledge = power” suggesting that in relation to museums his equation needed refining, as does the definition of “The Archive” because it isn’t a “unitary” phenomena. Archives are distinctive and function in different ways and the museum archive is something else again, “an archive of an archive”. “But”, she added, “the archive makes the museum, otherwise it is just stuff”. And while other organisations keep archival material because they “should”, museums “need to”. The museum archive systematises and organises unruly things and cannot be separated from them. To this end, all sorts of spaces, storage and cupboards are pressed into service, ad hoc and improvised, because in museums archives remain “subservient” to objects and may even be an after thought. Kate suggested that Foucault’s model of power is too simplistic for understanding the museum archive where logistics, recording practices and museum histories produce an “institution” that is not inert, so we “need to see the history of the archive”. Kate suggested reading “against the grain”, exploring “what can and can’t be said”, uncovering “problematic voices”. Controversy brings up varied voices; and “tone of voice” might change during an exchange of letters, while “annotations” can “go wildly off script”.

Documents also reveal “other players” and “recover…agency” within “networks of meaning”. Although Kate didn’t use the term Actor Network Theory, she had me thinking that was where we were heading. “Museum records aren’t intended to tell us about people at all”, she suggested, rather records attempt to define institutions, in a “static and stable” state, whereas in actuality they “unfold” over time. Also, whenever museums are judged newsworthy, influential or contested, the media extends the museum beyond its own space into public and private arenas.

When it comes to objects the archive’s role comes closer to Foucault’s “gate-keeper” paradigm; numbering, dating, “museum-ising” objects until they are no longer “free”. The record itself becomes an object, and Kate reminded us that “the form of records has a history too”. But that evolution and the use of technology doesn’t guarantee improvement; standardised forms and mistakes in data entry mean that information may be “disciplined” but is less stringent, less surprising too. Kate suggested that the “catalogue becomes constraining” as it changes from “form to form”, and digital versions with drop down menus might be the worst yet. If the basic aim of museum archives is to keep track of objects there have been monumental fails, “destroyed by pests” or simply “not found”, and there exists a “huge backlog” of cataloguing, which is mainly undertaken by untrained volunteers as unpaid “piecework”.

Kate ended with some “methodological thoughts”: understand the form and historical development of museum records, and that they are not absolutely accurate but may be “improvisations…records look more disciplined than they really are”; look for the unexpected and you’ll find the “limits of the set scripts”, and those improvisations, contingencies, dialogues and networks; move away from the “best documented” people and places, as a “collage…of scraps of information from different but similar objects” will provide “a better view of how museum records work to produce meaning”, refocusing attention on under-represented people and objects. And I’d add, underrepresented disciplines and “museum types” too, for example, design and design museums, because beyond the “best documented” (Victoria and Albert Museum) these are almost absent from the literature of Museum Studies and Museum Histories.

Before leading the final discussion Claire Wintle (University of Brighton) delivered a virtuoso recap. She reiterated the questions that need asking, including, what is the anatomy of the archive – official and unofficial – and suggested that going beyond the rules and the museum, to include media, oral histories and personal papers, will prove productive. And as record keeping technologies have changed over the centuries, archives reflect that diverse materiality in their complex anatomy; so, contradictions can be interesting if we ask why they exist. But, looking to the future, these collections will be difficult to digitise. Claire offered three final themes for the audience to think about: how we keep records today; how researchers and archivists can collaborate; and, what is it that museums want to know about their history?

What more can you ask from a day of listening than to be introduced to new information, sources and methodologies, as I was. That this event prompted me to recognise parallels between the speakers’ work and my own processes and progress also provided a sense of reassurance and a renewed impetus to test the edges, as they were doing.

A couple of observations. At this event, as at other relating to museums and archives, I’ve been struck by the fact that most of the speakers and delegates are historians, archivists, curators, sociologists, anthropologists and archaeologists who are engaging with material culture; museum objects, archives of objects and documents (which are objects too). Again and again I’ve wondered, where are the art and design historians (at least on the platform) and what more might they bring to this conversation, which foregrounds objects and images over texts as carriers of meaning. Is it that art and design historians are so familiar with “using” objects, museums and archives in their practice that they don’t need to enter these conversations? Or, do art and design historians inhabit a discrete arena separate from the mainstream of “history” in both the academy and the museum? Of course there are places where multi-disciplinary cross-overs and collaborations occur and individuals whose research interests inhabit that nexus. But I’m surprised that it doesn’t happen more often.

Secondly, I want to explain why I’ve recorded such close observations of a number of events. During this research project I’ve made an effort to attend as many events as possible. With a multi-disciplinary project (as mine is), and with over twenty years between finishing my MA and starting my PhD, I realised that attending events could prove an efficient way of tapping into current concerns across a range of subject areas and disciplines, e.g. who’s talking about what, with regards to, for example, digital histories, big data, accessing archives, using museum objects and heritage funding. Ultimately, these posts allow me to cite events in my research, as they insurance against the possible disappearance of online documentation, webpages hosted by institutions are often deleted to free up server space. I accept that my recordings of these events are partial, but as I’m recounting my impressions as an audience member and have included comments that connect topics directly to my research, there is no suggestion that these accounts are objective. Basically, I am acknowledging that these events have informed my research.

And, here’s a pdf of the programme, listing all the speakers and the titles of their papers…Using Museum Archives programme.