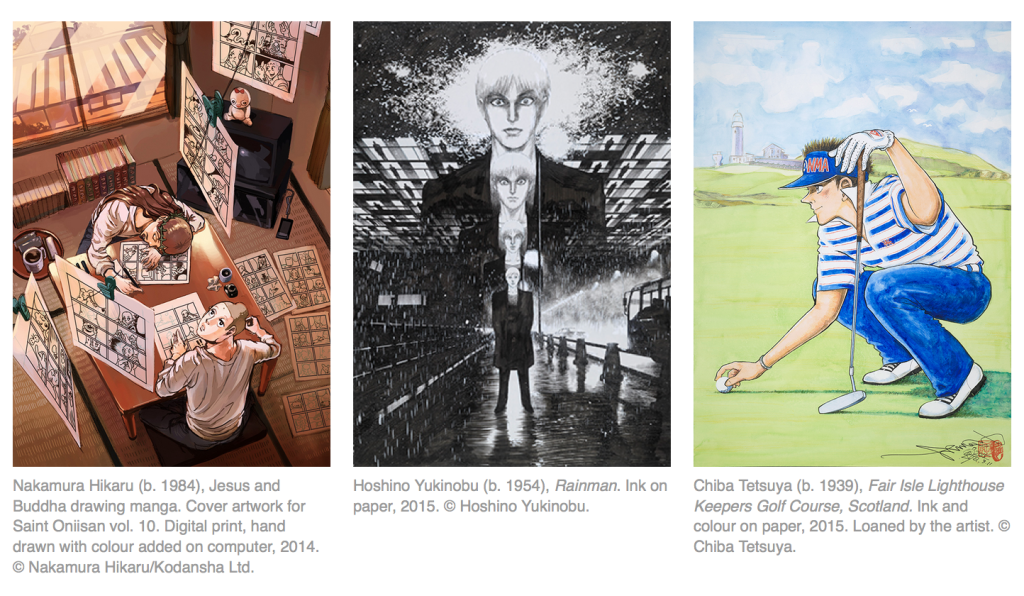

Manga is a popular choice for museum exhibitions and displays: with boundless variations in content and style, it’s accessible but (still) culturally exotic; it mixes scholarly research with contemporary collecting; and whether PG-rated or not, attracts a diverse audience of geeks and gawkers of all ages. Not for the first time, the British Museum gives over the high profile Room 3 (can’t miss it, first stop on the right) to a manga-moment with Manga now: three generations, which features new and specially commissioned work by Chiba Tetsuya, Hoshino Yukinobu and Nakamura Hikaru. I’ll pop in to inspect it next time I’m on the hallowed ground.

Manga now, three generations

The Asahi Shimbun Displays, Objects in Focus

British Museum

Great Russell Street, London WC1

www.britishmuseum.org

3 September to 15 November 2015

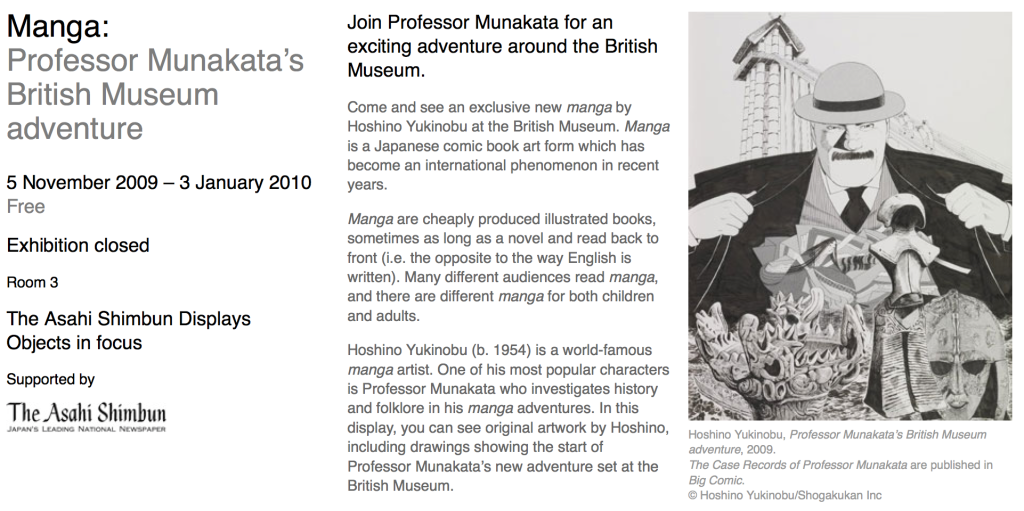

Previously the same gallery featured the stunning display, Manga, Professor Munakata’s British Museum adventure (5/11/09-3/1/10), by Hoshino Yukinobu. Jane Cheng reviewed that show on Eye, here: “The juxtaposition of hugely enlarged with minutely detailed asks visitors both to lean in closer and to step back”. Jane’s post features great images of the life-sized cut-outs in situ – like walking through a giant pop-up book — and she highlights the interactive nature of illustration exhibitions (something I recognised too at the V&A’s Memory Palace show, and featured in a conference paper, here). Loving a museum-based-mystery, especially one that showcases perfectly rendered images of museum objects (and hat’s off, what a tie-in, when’s the movie?), I ordered said graphic novel from the BM’s online shop having received a timely email reminding me of the publication on the same morning that the new show opened; now that’s what I call museum marketing. The online shop also tells customers, “Every purchase supports the Museum” (rather than Amazon).

All this manga activity has prompted me to re-post something I wrote for the print version of Eye, showcasing Adam Lowe’s exhibition and book. It was the first time I’d seen manga up-close and Adam’s selection was dark and difficult, far from the mainstream and not in translation. For more background on manga I visited his Thames-side warehouse, an artists enclave in pre-regeneration mode. The text is reprinted below, and can also be accessed via a search of Eye’s website, here. No images accompany the text, though, so instead here’s the cover of Adam’s book and the opening spread of the article (with art direction by Stephen Coates).

“Astro boy and the sex wars”

by Liz Farrelly

Eye

Issue 5, Volume 2, Winter 1991, pp.34-39

Manga are a uniquely Japanese phenomenon and the contemporary expression of a popular visual culture which dates back to twelfth-century caricature scrolls. Because written Japanese mixes four different alphabets (kanji, katakana, hiragana and roman) and is allusive rather than descriptive, a mix of words and images has become the favoured form for recreational reading. In 1988, 1.75 billion copies were consumed on the street, in restaurants, on commuter trains, and even in schools, where children are taught to read with manga.

Mangas are printed in four formats: as telephone directory-sized books containing weekly serialisations of stories, and as volumes of complete stories, available either as pocket-sized or standard-sized paperbacks, or as high-quality hardbacks. The range of content points to the diversity of the audience: financial news for businessmen, cookery for housewives, love stories, war stories, tales from traditional folklore, and hardcore pornography. Manga artists are national celebrities, prolific and well paid. Fans collect every story by their favourite artists, so publishers lure the big names with lucrative contracts. With further income from reissues, merchandising deals and animation rights, some artists make it on to Japan’s list of top earners.

Osamu Tezuka

During a career that spanned 40 years, Tezuka produced 500 stories and a total of 150,000 pages, which sold 100 million copies in paperback. Creator of Astro Boy and founder of Mushi Productions, the animation company that brought manga “anime” to a worldwide TV audience, Tezuka remains the undisputed genius of manga and the only exponent to be honoured with a retrospective exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. His epic story The Phoenix was serialised between 1967 and 1988 in three different weekly compilations. The Book of Civil War is the eighth of 11 volumes which investigate the human condition, immortality and spiritual beliefs. Tezuka’s framing techniques are most accurately described as filmic. The viewer’s eye is directed through a narrative that jumps around in time and space, viewpoints shift and sound effects leak into the margins. The resultant dynamic successfully emphasises the act of reading.

Kazuichi Hanawa

Traditional Japanese folklore and ritual provide the raw material used by Hanawa, who lives on the history-rich and still relatively non-industrialised North island. “The Tantrum”, from a two-story compilation, Red Sky, published in 1985 and reissued in 1989, is a nostalgic reminiscence of a trip to the acupuncturist by a naughty child and his mother, which provides an opportunity for comment on the definitions of tradition and modernity. Finely rendered rustic Japanese landscapes are invaded by nineteenth-century western technology and peopled with less realistically drawn characters. This discrepancy in technique is intended to provide viewers with enough visual information to enable them to enter the scene and identify with the characters. Sound effects are expertly handled by Hanawa, pushing the narrative along while requiring the minimum of effort from the viewer. Stories like “The Tantrum” flatter readers with a cosy reminder of Japanese history.

Mitsuhiko Yoshida

A training in print-making and experience as a theatre designer and illustrator have provided Yoshida with an aesthetic influenced by Edo period ukiyo-e prints that makes an effective vehicle for his uncompromising subject matter. Clear, precise, dramatically edited images describe psychologically loaded situations. Two stories from Paper Theatre, published in 1990, reveal a range of narrative techniques that frame stories about sexual awakening and paranoia. “The First Visitor” describes a young girl’s dream of being pursued by a rampaging phallic symbol, after she draws a picture of a rhino. Her father guesses she is about to have her first period, an event which is celebrated in Japan with a family gathering and the eating of red rice. This frank and sympathetic treatment contrasts with the explicit visual puns, arranged as a series of vignettes, which make up “Sex Wars”. Yoshida’s stories are designed to appeal to young men and any woman reading them would be considered to be liberal.

Keiko Takemiya

Despite the presence in many manga of extreme violence towards women, the industry doesn’t discriminate against female artists. The audience for “romantic” manga is one of the most loyal and avid sectors of the readership. Takemiya’s long-running serial, Le Poème du Vent et des Arbres, begun in 1976, tells of homosexual love in a French boys boarding school. The sentimental style contrasts with the darker message that romance and bullying go hand in hand.

Higirina Kouya

The latest signing to Kodansha, one of the largest publishers of manga, is the partnership of Atsushi Kikuchi and Tadashi Watanabe, who adopted the pen name Higirina Kouya. The End of the World (1990) contains one-page cartoons that are satirical comments on modern Japanese life. Many of the jokes rely on wordplay and are therefore untranslatable, but one example succinctly demonstrates how a child’s vision of the world can be horribly accurate.

Suehiro Maruo

Even though Maruo’s stories appeal to a predominantly male audience, and are full of sex and violence, they avoid being labelled “Juicy Manga” by the inclusion of knowing quotations from western art history that add an intellectual and aesthetic dimension to the narrative. Favourite devices include Daliesque floppy clocks and landscapes, Balthus-inspired pubescent girls, and well-known images from war photography. Maruo’s graphic techniques are similarly diverse: clear linear drawing, scratchy expressionistic rendering, grainy photographic backgrounds and obsessive pattern-making can all appear in the same story. National Kid, published in 1989 and re-printed in 1990, is an anthology of stories which deal with sexual fantasy, Nazism and childhood fears by randomly juxtaposing images that defy readers to create their own narrative. The Japanese characters floating across one troubling image simply make a squelching noise.

Manga, published by Lowe Culture (1991), contains essays by Adam Lowe, Paul Gravett and Helen McCarthy. It accompanied the exhibition Manga, Comic Strip Books from Japan, selected by Kyoichi Tsuzuki and Alfred Birnbaum, curated by Adam Lowe, for Pomeroy Purdy Gallery, London, 11/10 to 9/11/1991.