I’m taking some time this summer to document activities over the last few years, including occasional academic papers delivered at conferences and workshops. Images are from PowerPoint presentations and include quotes projected so as the audience can read along with references in the text. This paper was delivered “live”, and although it’s been re-edited for the page, I decided not to include footnotes or formal citations; all documents referred to are in the Design Museum archive, which is being catalogued, and mentioned texts are listed at end. This is a work-in-progress relating to my doctoral thesis, so if it feels truncated that’s because I’m using this blog as an “ideas store”, with the intention of expanding and deepening my arguments in the thesis.

Curating Popular Art

Whitechapel Gallery

77-82 Whitechapel High Street, London E1

14 June 2013

Organised with the University of Brighton Design Archives; a study day to accompany the exhibition

Black Eyes and Lemonade: Curating Popular Art

9 March to 1 September 2013

As the recipient of an AHRC Collaborative Doctorate Award, pairing the University of Brighton with London’s Design Museum, I’m looking at how definitions of design are produced and evolved within museums.

Good Victorian that he was, Henry Cole’s aim as founder of what is now the Victoria and Albert Museum, was to create an institution that informed manufacturers, workers and the public about the benefits of “good design”, so as to encourage the production, consumption and export of well-designed and efficiently-made “everyday” products, which would reinvigorate British industry. Jump to 1917, and Hubert Llewellyn Smith, Head of the Board of Trade and an early advocate for design education and design promotion suggested that a new museum of industrial design would help this cause. (The Board of Trade went on to set up the Council of Industrial Design, later the Design Council, and administrated the Victoria and Albert Museum up until the early 1980s). Such rhetoric around design promotes a series of promises; that “good design” will facilitate economic development, cultural innovation and social improvement. This discourse of design promotion has been central to the growth of institutions dedicated to the collection and display of designed objects. I’d suggest that now there is a more pressing need to present a truly comprehensive vision of the role and benefits of design; instead of “good design” might we consider “design for good”? But are design museums still fixating on Cole’s vision? Promoting individual designers and showcasing “the best” products of the year may fulfil the aims of a design museum, but explaining the design process and its multifarious activities and outcomes – showing design to be a tool for engagement and change – would more closely demonstrate “what design is now”. So, when it comes to design in museums, we are on the cusp of change.

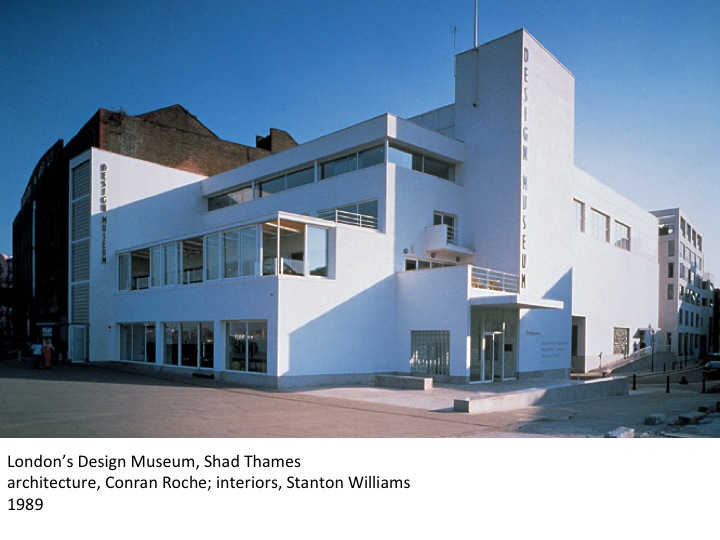

At the turn of the 1980s, the first steps to establishing a stand-alone design museum in the UK were taken by an educational charity, the Conran Foundation, which funded the Boilerhouse, a temporary exhibitions gallery, housed in the V&A, focusing on mass-manufactured objects and steeped in that historical rhetoric of design promotion. That actually put it at odds with the more connoisseurial tenor of the V&A at the time, and it was a less than welcome “squatter”. (I investigate this culture clash in detail in my thesis). By 1989, renamed the Design Museum, it had relocated to a “modernised” warehouse in Shad Thames. Now, plans are well underway for the museum to grow and move again (original date 2014, rescheduled to September 2016) to the Parabola in Kensington (previously home to the Commonwealth Institute).

In contrast to many of the UK’s publicly run cultural institutions, the Design Museum is, essentially, an SME (a privately-owned, small or medium-sized enterprise), employing 45 curatorial, managerial and administration staff and 30 front-of-house volunteers. (Since writing this, the staff has almost doubled as the Museum implements its planned expansion). Annual visitor figures have fluctuated between 150,000 and 300,000, which is about one-tenth the size of a national museum. The audience is unusual too, because although it includes a diverse range of people, including school children, tourists and families, about 60-70 per cent of the visitors are design students and professionals, directly involved in the museum’s subject area. These statistics were provided by Dr Helen Charman, Director of Learning and Research, and are based on figures compiled by a market research company commissioned by the Museum. That high percentage contrasts with what Lynn D. Dieking and John H. Falk, experts on Visitor Studies, identifies as more usual, with just 7 per cent of a museum’s visitors categorised as “professional or hobbyist”, i.e. having a direct stake in the content on offer. Despite its size, then, the museum is an important resource for those with a stake in design. By implication, its exhibitions, collections, events, workshops and website, plus its mission statement, annual report, surveys and questionnaires, visitor feedback forms and educational material, all imply an understanding of design, colour definitions of design (I don’t think there is just “one”) and contribute to the formation of the discourse of design. We could keep posing the perennial question, what is design?, but I’m more interested in looking at how the museum itself answers that question.

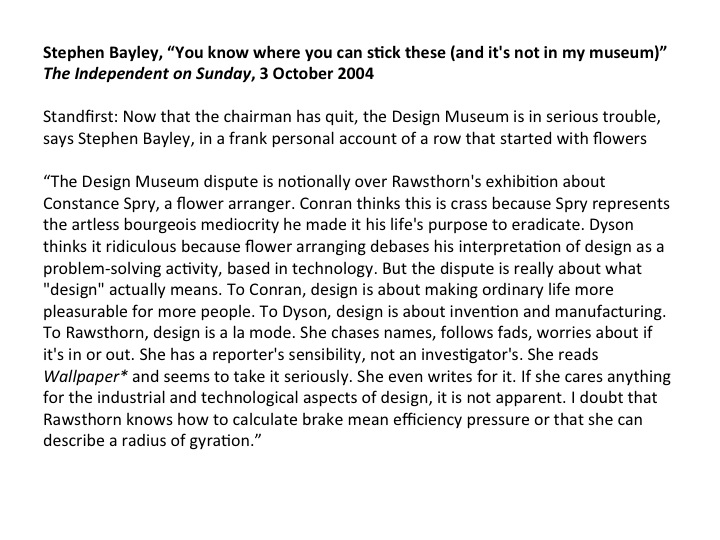

In case you’re wondering about the source of the quote in my title, it’s from Stephen Bayley; to give it it’s fully title “You know where you can stick these (and it’s not in my museum)”; it appeared in The Independent on Sunday, 3 October 2004. Bayley had been associated with the plan to create a Museum of Industrial Design since 1979, working with Sir Terence Conran (founder of the Conran Foundation and the Design Museum). Bayley was the founding Director of the Design Museum, though he chose the title, Chief Executive. But this article appeared 15 years after he resigned from the post, just two months after the Museum opened. In that light, the declaration by Bayley, of “Not in my Museum!” is a highly provocative statement. How is it Bayley’s museum? And while this article is ostensibly a review of the London Design Museum’s exhibition, Constance Spry: A millionaire for a few pence, Bayley uses it to launch a comprehensive attack on the Museum’s Director, Alice Rawsthorn, her exhibition programme and, by implication, her definition of design.

Again, disproportionate to its size, media coverage of the Design Museum is impressive; boosted perhaps by having three Directors (out of five) work as journalists, each being critical of the museum both before and after their tenure. Add the fact that Conran, the Museum’s founder, has been an outspoken advocate for design since the 1950s. So, if there’s a row in the offing, it’s news-worthy and it will go public. Criticism, tension, rows, walk outs, and resignations, these constitute key moments of what I call “institutional friction”; these manifestations of ideological difference between protagonists, acted out, in real time, in the museum, invariably lead to change, a “great leap forward” or a “backward retrenchment”. Either way they evolve the museum’s aims and its definition of itself and of design.

Which is where the flowers come in…

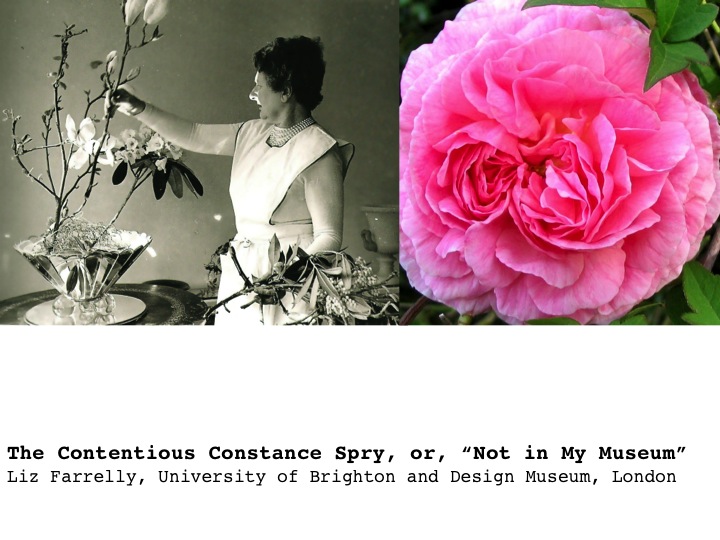

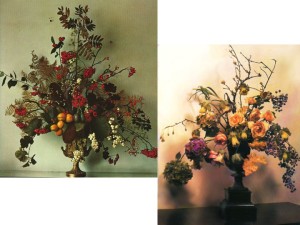

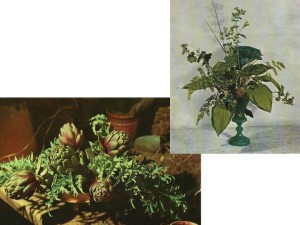

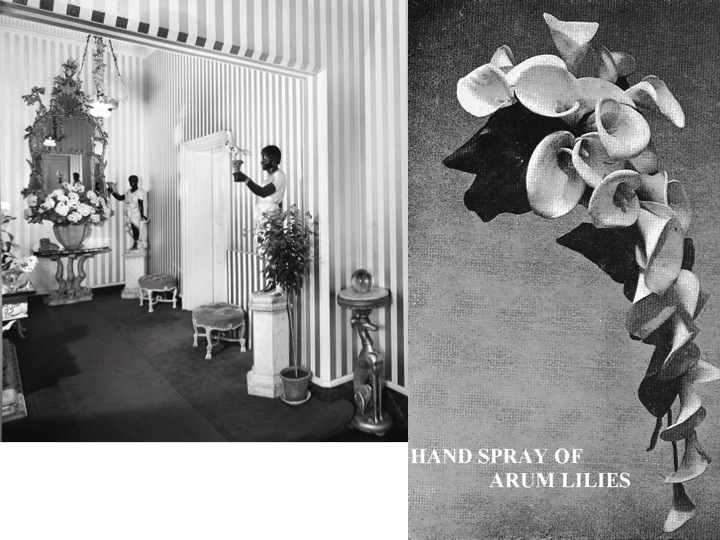

…I just want to show a few examples of Constance Spry’s floral decorations, using what some contemporaries considered to be “stuff that should go with the wheelbarrow”. Her signature approach was to create unexpected combinations of all sorts of plants – flowers, foliage, grasses, fruit and vegetables – making use of containers both precious and mundane; I think her approach looks spectacular and unconventional, even today.

Back at the Museum: I’d suggest that a key period of “institutional friction” comprises a number of linked incidents, between 2004 and 2006, starting with: Sir James Dyson’s resignation as Chairman of the Board of Trustees; followed by the media coverage around the Constance Spry exhibition, which fanned the flames; and finally, the departure of the Director, Alice Rawsthorn. This “rift and shift” began when Dyson voiced his concern over the museum failing to remain “true to its original vision”, which, according to Conran was “to explore the industrial design of quantity-produced products”, an aim unequivocally informed by Cole’s rhetoric about the economic importance of design, and all subsequent efforts at promoting design as a cure-all for industrial decline.

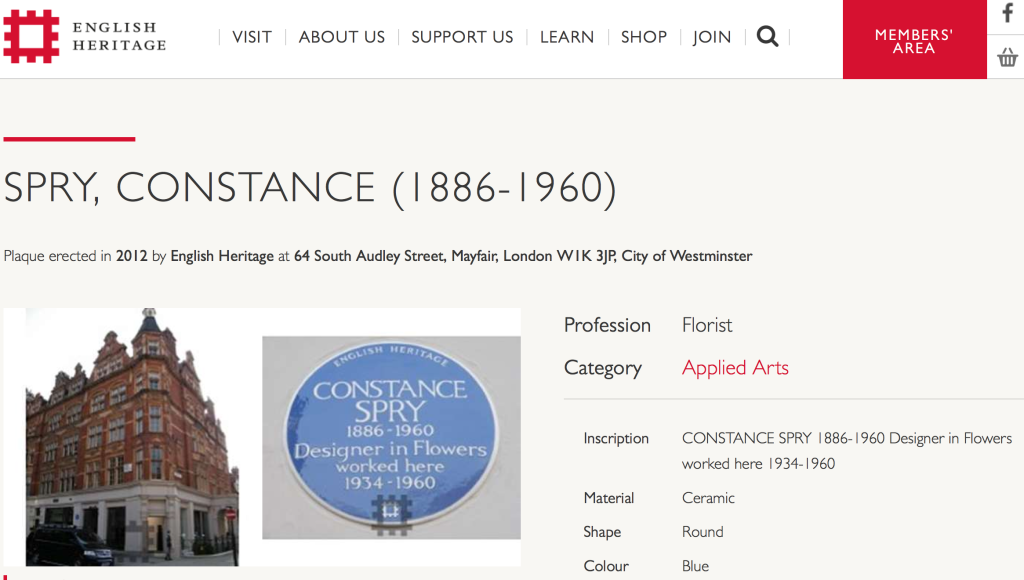

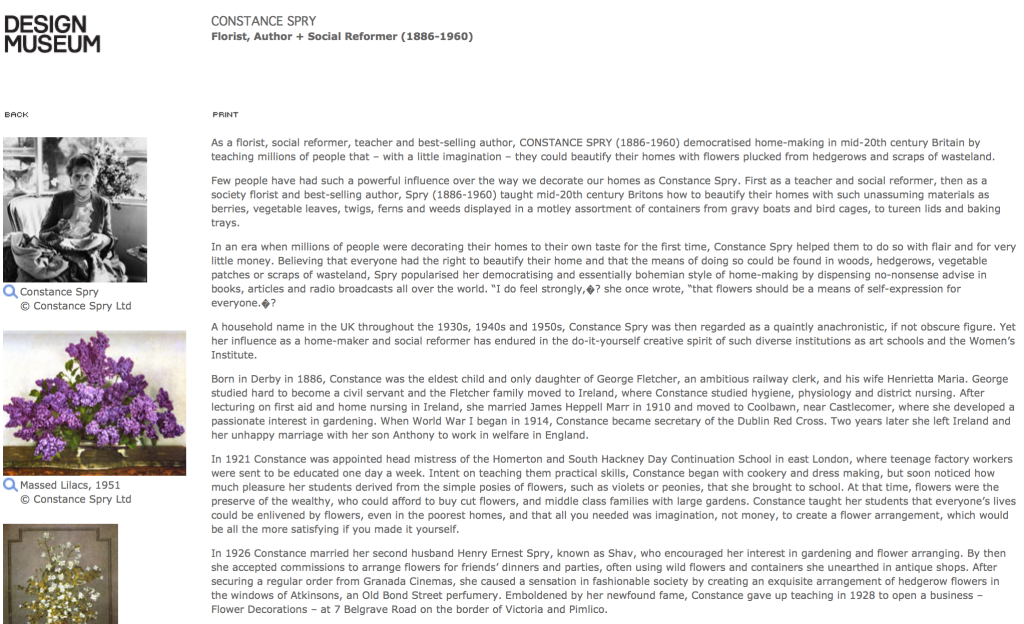

Dyson is vocal about his disapproval of a number of exhibitions staged during Rawsthorn’s tenure, but the one that becomes a focus, and effectively fuelled the row, featured the “designer in flowers”, Constance Spry, which is how English Heritage describe her on the Blue Plaque commemorating the site of her famous West End shop. Spry was a champion of domestic creativity and a household name in Britain and the USA from the 1930s through the 1950s. So, by staging this exhibition the management and curators of the Design Museum were making a clear statement about what they considered to be worth showing in the museum, and therefore what might be defined as design.

The Curator flagged up issues of consumption, gender, popular crafts, amateur creativity, the use of ephemeral materials and the manipulation of nature, which, still untamed crossed the threshold into domestic space. These issues demonstrate an awareness of how the discipline of Design History was evolving into a cultural and social discourse, beyond a previous focus on production, industry and named designers. Whether the exhibition fully delivered or not, it certainly butted up against a contrary, object-centric ideology, held by elite members of the Museum’s community; hence the “institutional friction”.

Nearly a decade on and this remains a sensitive issue, and my methodology take this into account. I’m using three sources for information: the Design Museum’s archive, which is (sporadically) accessible and as yet only fractionally catalogued; interviews with individuals involved (and these are still ongoing); and media coverage, which is extensive, and includes broadsheets in the UK and US, the international design press and two articles in academic journals (the articles mentioned here are just the tip of the iceberg). A major issue with such a case study is, how do you reconstruct, reconsider, document and analyse a temporary exhibition once it’s over? For example, during interviews on the record and conversations off, I’ve heard contrary views of where and when the idea for this exhibition came about. Following the advice of Dr Linda Sandino, a design historian with extensive experience in recording oral histories, instead of questioning the veracity of differing versions of events, the aim is to “triangulate” sources so as to highlight consensus and disparities.

Before I go into detail about the exhibition, I want to suggest that the furore over Spry reveals deep-set divisions regarding aims and beliefs: about what the Design Museum should and could be; about management and funding; the definition of design that key personnel wished to promote; and about how any definition of design might be informed by questions around gender. Ultimately, though, the very public row around the Spry exhibition, in effect, created a smoke-screen behind which a power struggle for control of the museum was playing out.

Back to the case study. Design historian, Dr Deborah Sugg Ryan, working as a freelance curator had previously staged an exhibition about the Ideal Home Show at the Design Museum, which was enthusiastically received by press and audiences, but disparaged by Conran as “ugly”. In an email exchange in February 2004 initiated by Rawsthorn, she refers to a meeting three months earlier when Sugg Ryan proposed an exhibition on Constance Spry, but supposes that teaching commitments prevented her from producing a written proposal, which had been invited; so, the discussion had faltered. When a gap appears in the exhibition schedule, Rawsthorn writes to inform Sugg Ryan of the proposed dates for the show, and that the project is going ahead. This might be considered a cavalier attitude to the ownership of an idea, but it also points to the practical problems of working with freelance curators who, as academics, have full time-tables for nine months of the year. It’s worth considering that, based on Sugg Ryan’s subsequent critique of the exhibition, her vision for the show was more comprehensive, necessitating fund-raising, primary research, a significant “build”, and a longer time frame, to produce a very different output from the exhibition that was actually staged.

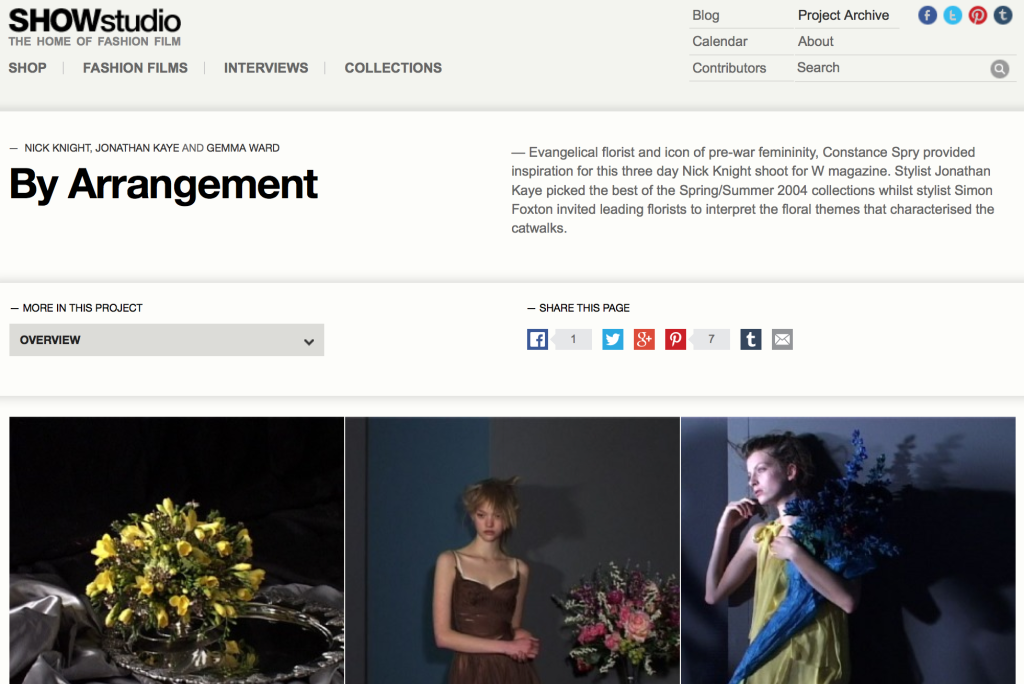

Libby Sellers curated Constance Spry: A Millionaire for a Few Pence (17 September to 28 November 2004), while employed at the Design Museum. The title refers to one of Spry’s 11 published books. Sellers recalls a photo-shoot by Nick Knight, By Arrangement, posted on SHOWstudio on 27 November 2013, which used Spry as inspiration. She recalls how this was a starting point for her and Rawsthorn’s investigation into Spry’s legacy. Sellers mentions that there was a programming gap because of a cancellation. This may have been due to Rawsthorn refusing a show that Dyson had ear-marked without proper consultation (as mentioned in a later email exchange between Rawsthorn and Conran). It was reported in the Observer, that Spry was swopped for a show Conran had preferred but Rawsthorn had cancelled: Deyan Sudjic suggested that, for Dyson, it was “the last straw” (3/10/2004).

Sellers recalls having just months to organise a “narrative”, culled from an extensive but uncatalogued Spry archive. Such a pressing need ruled out Sugg Ryan’s involvement. In Seller’s own words…

…and so did the Design Museum team (working with graphic designers Kerr Noble), as they had a fraction of the usual budget for a show.

Beyond the extensive press coverage of the exhibition you’ll need to look hard for other extant traces. No catalogue was produced but Spry does have a presence on the Museum’s website, listed in “previous exhibitions” and now (since the resent redesign) via a link to the “Design Library”, which is a compendium of designers’ biographies, of individuals featured at the Museum. Spry’s biography, however, is peppered with inaccuracies and the page contains no mention of the exhibition nor any installation shots, although there are images in the archived exhibition folder. (I don’t have permission to reproduce images from the archive).

Meanwhile, a review by Sugg Ryan in the academic journal, Home Cultures, reminds us: “What has been missing from the coverage of the Spry Design Museum furore is a serious critical consideration of the exhibition itself”. What Sugg Ryan describes in detail is more of a display than an exhibition, installed in the furthest corner of the museum. It comprised text and photo panels, a small selection of vessels designed by Spry and two floral displays, which appear to be “untypical” of Spry’s work. Sugg Ryan concludes that the exhibition is not only a missed opportunity to examine the legacy of an influential taste maker, but that it misrepresented Spry’s work.

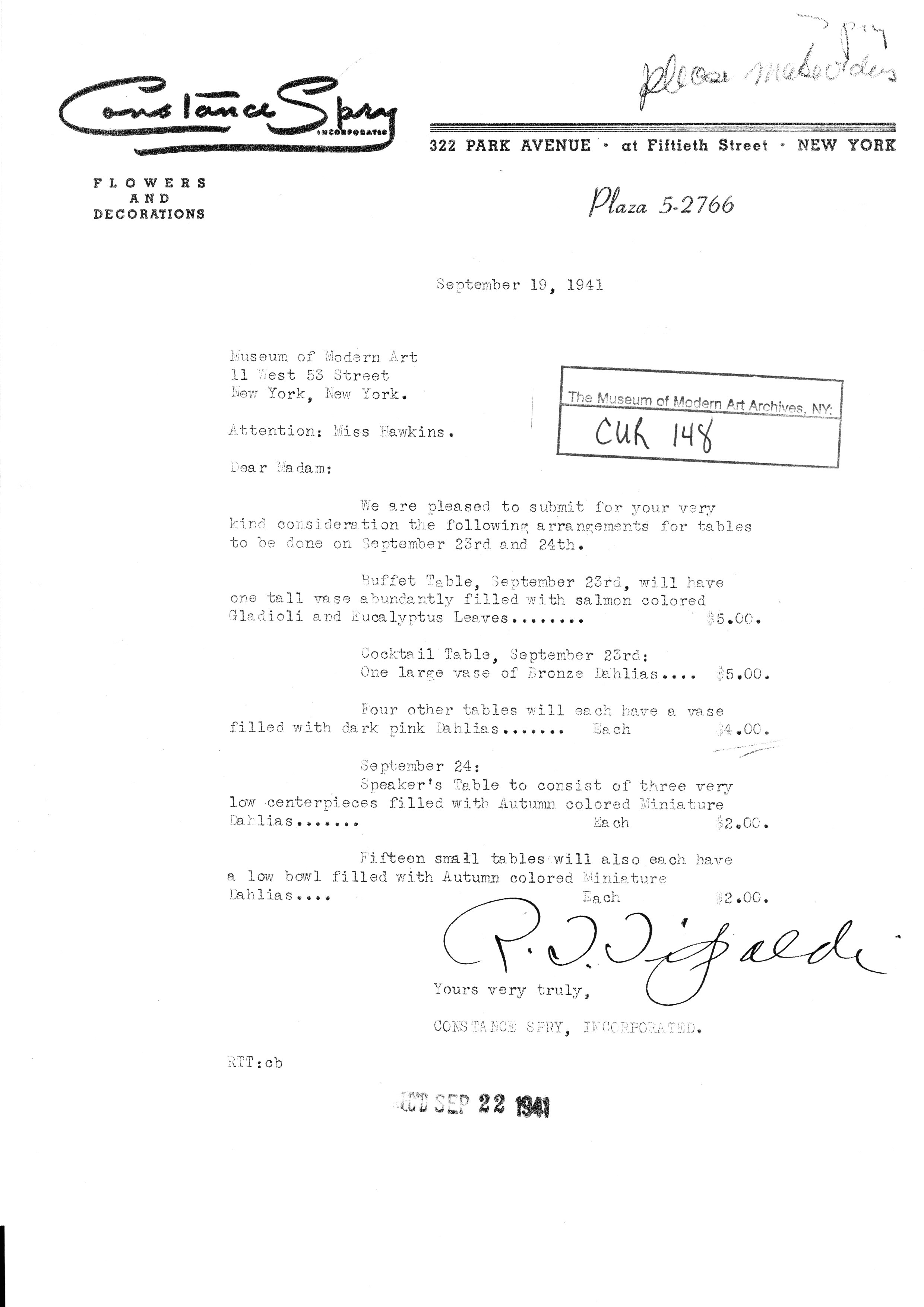

This slide shows an interior by a regular Constance Spry collaborator, Syrie Maugham, and includes more typical Spry floral decorations along with Oliver Messel figures. And, crossing-over into the world of fashion, a cascading wedding boutique, which was a Constance Spry innovation. Since giving this paper, some of the inaccuracies in the Museum’s online biography have be corrected, further legitimizing Spry’s role within a history of “high design” by emphasising links to a raft of feted practitioners. During a prestigious career Spry also collaborated with photographer Cecil Beaton, and her floral decorations appeared in domestic and retail interiors and entertainment venues (including the Royal Opera House and the Granada cinema chain). She also worked closely with illustrators, photographers, printers and publishers developing new techniques in colour reproduction and printing for her books and magazine articles. And, during a visit to MoMA’s archive in New York, I found a letter from her New York store confirming Spry’s contribution of floral displays for the events around Organic Design in Home Furnishings (1941). This landmark exhibition introduced the world to Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen’s experimental plywood chairs, which also entered the Museum’s permanent collection and the canon of “good design”. Spry spent several months each year in New York; to be considered aesthetically and socially compatible with the Museum of Modern Art conferred an avant-garde/artistic seal of approval on Spry’s work.

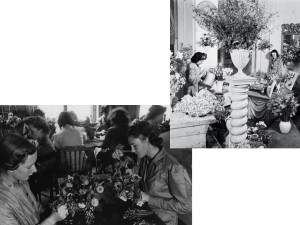

Adding a few more tantalising details; Spry “did the flowers” for Edward Windsor and Mrs Simpson’s wedding, and (proving her diplomatic skills) also designed the capital’s floral displays for Elizabeth II’s Coronation. A celebrated horticulturalist, Spry amassed what was at the time the largest collection of British roses, saving many from extinction. During the war she advised the UK government on nutrition and allotments, and post-war, developed new design standards for textile exports. All of this demonstrates one facet of her career – Spry was a design “professional” – and that alone should guarantee her presence within the “canon”. But another version of Spry’s “history” might question that canon by emphasising a more inclusive definition of design; her encouragement of creative homemaking through books, magazine articles and demonstrations, and her role as teacher, mentor and adviser to women of all ages and classes, through the National Association of Flower Arrangement Societies. I’d suggest that it was this role that really earned her that Blue Plaque.

Search the arts and humanities library at the University of Brighton, and Spry is the only subject of a Design Museum show NOT represented on the shelves. Why: perhaps because she defied neat categorisation and had no formal design education in a easily defined design discipline; perhaps because she worked with ephemeral media, flowers and food, not steel and concrete; or because her achievements were perceived as within the female realm, as “women’s work”? One consequence of Spry’s “miss-fit” (literally) status is that this exhibition became the site of an ideological power struggle, between a Director who was taking the Design Museum in one direction (albeit tentatively), and certain members of the Board of Trustees who resisted that change. In an email to the Constance Spry company archivist, when confirming loans to the exhibition, Rawsthorn describes the Design Museum as having “a mission to excite everyone about design”, and the Museum’s role as “a map and mirror…of design in the broadest sense of the word”.

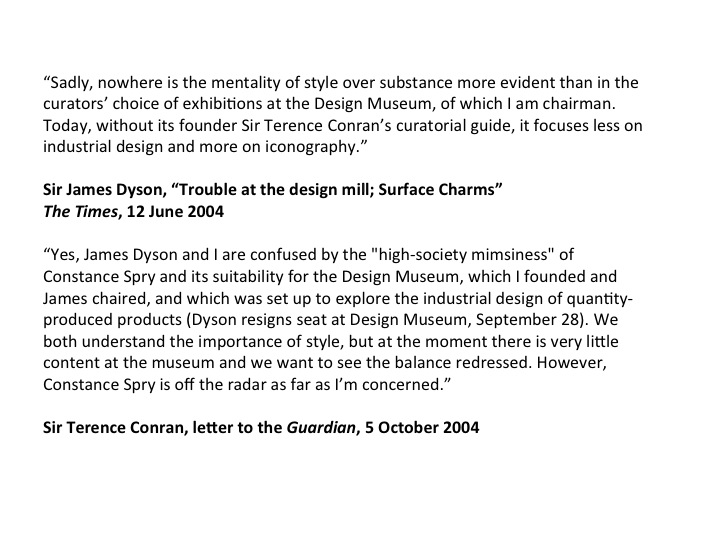

Contrast this view of the Design Museum with Dyson’s. While Spry was still in the planning stages, and he was Chairman of the Board of Trustees, he wrote an article, “Trouble at the Design Mill: Surface Charms” for the Times (12 June 2004). In it he declared there to be no difference between industrial design and engineering, it’s what “made Britain great”. Cole would be proud, but, he goes on to say that design has become “dislocated” from industry, and, “Sadly, nowhere is the mentality of style over substance more evident than in the curators’ choice of exhibitions at the Design Museum…”

That’s a surprising statement considering the Spry show ran concurrently with two larger exhibitions that contained both engineering and industrial design; E-type, the story of a British Sports Car and a retrospective of superstar designer, Marc Newson, known for his luxury yacht and private plane fit-outs. In actual fact, Spry provided a degree of balance to this “boys own” world. But balance is what Dyson thought was missing from Rawsthorn’s programming, which he criticised as featuring “fashion, styling and fads”, rather than “the hard stuff” (his words). Backing up Dyson, Conran wrote a letter to the Guardian (5 October 2004) after the Spry show opened, reiterating Dyson’s views and repeating his original reasons for founding the Museum. Regarding Rawsthorn’s style over content programming he “wants to see the balance redressed”, while managing to ignore the not insubstantial presence of a F1 racing car in the adjacent gallery.

Just days before, Sudjic (then the Observer’s design and architecture correspondent, now the Director of the Design Museum) reported (3 October 2004) that Dyson was using the exhibition as an opportunity to protest, after fellow Trustees refused to back his attempt to reign in Rawsthorn’s authority. Dyson (in alliance with Conran) had demanded that all programming be approved by the Trustees, while trying to impose his own selection of exhibitions on the board; Rawsthorn refused on both counts. So Dyson went public: “even though he had agreed to keep quiet for the sake of the museum”, reported Sudjic. Dyson’s resignation statement claimed that the museum was “no longer true to its original vision”.

As reported by Jonathan Glancey in the Guardian (28 September 2004), Rawsthorn was fundraising with some success. She had also increased visitor numbers and revenue, her tactic being to raise the museum’s profile by staging popular shows on world-class brands and designers such as Nike, the shoe designer, Manolo Blanik, and milliner, Philip Treacy, then deepen and widen the programming. In 2004, 88 per cent of visitors polled said they would return for another visit. Perhaps Rawsthorn was close to being able to fund the Design Museum without Conran’s financial backing, which would, presumably, limit his decision-making power within the institution. And while it was Dyson who “went public”, page after page of newspaper coverage talks about the Museum being “brought into disrepute”, because of “such a public row”, as Sudjic put it; the implication being that Rawsthorn had been disruptive, with the row was blamed on her reluctance to compromise. Sudjic’s prognosis was that: “The museum will find fundraising much harder”, adding that Conran would again be asked to inject cash into the Museum. Then came the personal attacks, with Bayley’s Independent on Sunday (3 October 2004) article referring to Rawsthorn’s marital status and personal preferences (teetotal), and that (in his opinion) her fondness for a particular West End restaurant, “the Ivy”, denoted a wholesale acceptance of “celebrity culture”. Meanwhile, Janet Street-Porter, in The Independent (30 September 2004), suggested that Rawsthorn, a renowned design journalist, was unable to differentiate between design and fashion. While both these articles claimed to “define” Rawsthorn through her cultural and social preferences, and her presumed lack of understanding of design (which is afforded a higher status than fashion or popular culture), much of the media coverage around the exhibition reveals that not only was Constance Spry under attack, as an interloper in the rarefied world of design and its museum, but so too was Rawsthorn.

Along with a clash of ideologies, regarding the definition of design, and role of design promotion within museums, this crisis reveals differences in management style that may be an inevitability within a “private museum”. During the curatorial process, Rawsthorn tells the Spry Archivist: “Having discussed the matter with colleagues at the museum, I am delighted to confirm that we would love to go ahead with an exhibition on Constance Spry’s work and legacy”. Whatever the realities of the curation process under Rawsthorn (or any other director) her tone of consensus and inclusion contrasts sharply with comments by Bayley, Dyson and Conran, which resound with an outraged sense of impinged ownership. The role of a museum’s Board of Trustees is to be final arbiter of a museum’s programme, not the instigator; by contrast the behaviour of Dyson and Conran is more akin to the power play enacted within a commercial company’s Board of Directors, their more usual habitat.

A storm in a tea-cup perhaps, especially considering the size of the display that ostensibly kicked it off. Through analysing this row, though, I became aware of alerted me to the prevalence of institutional friction within museums across sectors and irrespective of scale (and I explore this more thoroughly in my thesis). While a high profile museum row sparked by exhibiting the Enola Gay at the Smithsonian Institute led to the departure of a museum director and gained column inches in newspapers and academic journals, such events are not always well documented, but they aren’t rare either. Beyond who runs a museum, with whatever personal or professional agenda, other fundamental issues are at stake. For while institutional friction can be emotionally and professionally disturbing, it inevitably leads to change – whether a leap forward or a backward retrenchment – that will affect the aims, mission, methodologies and definition of a museum, as expressed through its content and programming. In the case of the Constance Spry debacle at the Design Museum, the choice seemed to be between a prescriptive and restrictive attitude or an expansive and inclusive approach. That the Museum has evolved beyond any such polarisation points to the development of increasingly robust management structures, part of the Museum’s next move.

References

Bayley, Stephen “You know where you can stick these (and it’s not in my museum); Now that the chairman has quit, the Design Museum is in serious trouble, says Stephen Bayley, in a frank personal account of a row that started with flowers” in The Independent on Sunday London: 3/10/04, p17

Burton, Anthony (1999) Vision and Accident: The Story of the Victoria and Albert Museum London: V&A Publishing

Charman, Helen (2011) The Productive Eye: Conceptualising learning in the Design Museum Institute of Education, University of London, unpublished thesis

Conran, Terence “Letter: Concepts of design” in The Guardian London: 5/10/04, p21

Dieking, Lynn D. and Falk, John H. (1992) The Museum Experience Washington, DC: Walesback Books

Dyson, James “Trouble at the design mill; Surface Charms” in The Times London: 12/6/04, p7

Gieryn, Thomas F. (1998) “Balancing Acts: Science, Enola Gay and History Wars at the Smithsonian” in Macdonald, Sharon (ed.) The Politics of Display: Museums, Science, Culture London: Routledge

Glancey, Jonathan “Dyson resigns seat at Design Museum: Jonathan Glancey on a clash of styles and ideology” in The Guardian London: 28/9/04, p5

Lewis, Neil A. “Smithsonian Substantially Alters Enola Gay Exhibit After Criticism” in New York Times New York: 1/10/94

Macdonald, Sharon (ed.) (2011) A Companion to Museum Studies Oxford: John Wiley & Sons

Sandino, Linda (2012) “A Curatocracy: Who and What is a V&A Curator?” in Hill, Kate (ed.) Museums and Biographies: Stories, objects, identities Rochester, NY: Boydell Press

Shephard, Sue (2010) The Surprising Life of Constance Spry London: Pan Books

Staniszewski, Mary Anne (1998) The Power of Display: A history of exhibition installations at the Museum of Modern Art Cambridge MA: The MIT Press

Street-Porter, Janet “Design and fashion aren’t the same thing” in The Independent London: 30/9/04, p41

Sudjic, Deyan “Review: Arts: How these flowers caused fear and loathing at the Design Museum: Should the Design Museum celebrate floral displays or feats of engineering? The resignation of James Dyson reveals a long-simmering row between director and trustees, reports Deyan Sudjic” in The Observer London: 3/10/04, p5

Sugg Ryan, Deborah “Exhibition Review: Constance Spry, a millionaire for a few pence” in Home Cultures Vol. 2 No. 1 2005

Thompson, Christoper (2008) Governmentality and Design: Inventing the industrial design councils of Great Britain and New Zealand University of Brighton, unpublished thesis

Archives

Design Museum Archive

Museum of Modern Art Archive

University of Brighton Design Archive

V&A Archive

Websites

https://designmuseum.org/

https://showstudio.com/