On the occasion of Paul Davis’s latest exhibition reviewed on the Eye blog, here’s a reminder of an earlier show that I was privileged enough to stumble across…

…and if you’re in Tokyo, you’ll find Paul drawing a…

Line in the Sand

at

Ginza Graphic Gallery (ggg)

DNP Ginza Building, 7-2, Ginza 7-chome, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0061

Until 28 February 2015

Monday 12:47pm, 1 June 2009

“Paul Davis wakes up in Brighton”

by Liz Farrelly

Eye Blog

On first viewing, Paul Davis’s exhibition of word drawings felt a tad bleak, on a sunny Friday afternoon wind-up to a Bank Holiday weekend, during the Castor + Pollux Private View right there on Brighton’s holiday-making seafront, with pleasure jostling business for attention. A few days later I revisited the work to discover more light among the shade.

Is this a new thing, I ask; where are Davis’s familiar characters; the crouching, naked women and bored IT workers? Putting aside his shaky figure drawings, which perfectly illustrate human vulnerabilities, Davis has gone for the jugular, using simpler means – single words, lines, blobs of colour – to achieve unadulterated communication.

“I’ve always made word drawings and used diagrams; I’ve got boxes of them at home”, he answers, then explains his fondness for the Venn Diagram. “There’s black on one side, white on the other, and grey in the middle”.

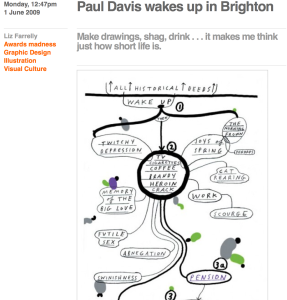

With drawings titled “Eventual deluded failure” and “A possible childless outlook”, the latter a culmination of “the last thirteen billion years”, Davis is tackling the big issues: sex, death, morality. “As you get older, you want to work things out, ‘essay’ out a point”, he adds. But he’s also recording the minutiae; “Walk to work” notes “shit & snot & shit”; while the life of a freelancer is unravelled in “Get up”, reading like the screenplay of a short film where nothing much happens, “… nervously checking emails…watching TV all day…” [I relate].

Davis culls these comments, emotions and attitudes from a range of sources: “TV, news, books, on the bus, I just listen to people moaning…life is annoying”. His word play is clever, funny, playfully twisted. “Your good self” is one drawing, “Your good shelves” is another; the plan chest in the middle of the page offering cubbies for such deeds as “murdering an appalling boss”. This is dark humour, but with a glimmer of silver lining.

To marshal all these thoughts Davis adopts a variety of explanatory formations. In “Unrelenting problematics”, a central lozenge is cut up into compartments with smaller, linked bubbles floating around, containing differing attitudes and outcomes. In another drawing, opposite extremes are demarcated by horizontal lines at the top and bottom of the page, with arrows denoting upward growth or downward spiral, you choose. Over here, intersecting bubbles joined by a spaghetti of curly lines, ostensibly linking ideas while actually complicating issues. Every now and then, colour, ink and paint make an entrance, either floating, blissfully unaware, or heavily gestured onto the paper in a defiant mood.

Much of this work comments on the need to create and the difficulties of achieving artistic and financial success alongside deeper emotional happiness: “The most important joy is the joy of making”, offers Davis. His own words and thoughts are here too, as not all of these stances are collected. “I blame existentialism, and those bastards who made you read it at school”. To underline his point Davis launches into the “Tomorrow” speech from Macbeth. “I love Shakespeare”, he adds, “…it makes me think just how short life is: make drawings, shag, drink…it kind of makes sense…”

Of all commercial artists, illustrators are the most bound up with the literary word/world. After all, they’re expected to read what they illuminate. And, even though Davis stresses that only ten per cent of his work is illustration, other literary exploits keep him busy: Davis is Drawings Editor of The Drawbridge, and works alongside Creative Director Stephen Coates (Eye’s founding Art Director). The quarterly broadsheet described as “in turn, critically nonsensical and radically serious”, offers essays and images on a changing theme. How do they choose? “We [the editorial team] talk about it, go for drinks at Blacks and come up with a word. It’s one word”, stresses Davis, “…it lets people breathe”. Working beyond the constraints of a commission is what gives Davis room to breathe. “I think you have to think”, he offers, then waits a beat and lets out an easy laugh.