This blog is intended as a place for comment on a wide range of activities, but specifically, it is an adjunct to my doctoral research so I’ll be posting interviews, reviews and articles about contemporary design in museums. The following is extracted from a longer interview with a Curator at London’s Design Museum, which will feature in my thesis, but also relates to my on-going interest in visions and versions of the future.

Neon welcome sign/exhibition logo hangs over laser-cut graphic of an industrial/technological timeline and points towards the Future Factory

The Future is Here

Design Museum

Shad Thames, London SE1

24 July to 29 October 2013

Alex Newson interviewed by Liz Farrelly, 2 December 2013

Installation shot of The Future is Here with Exhibition Design by dRMM Architects and Graphic Design by LucienneRoberts+

The Future is Here grew out of conversations between the Design Museum’s Director, Deyan Sudjic, and David Bott, Director of Innovation Programmes at the Technology Strategy Board (TSB), the UK’s innovation agency, which invests in new technology for the UK Government. The TSB backs start-ups with the aim of creating new manufacturing jobs. Wanting to do more than simply promote a string of TSB projects, Curator Alex Newson hit on the idea of telling the story of the “Third Industrial Revolution”. He opens the show with an historical “time line” of inventions and scientific breakthroughs, that have fuelled industrial manufacturing from the early 18th-century to today; a “Future Factory” is installed at one end of the gallery; and a wide array of exhibits explore a range of new technologies, and include: customisable dolls delivered by post (Makie dolls); compostable trainers, demonstrating that “unmaking” may be customised too (InCycle by Puma); and a crowd-sourced sofa, designed and voted on my the public and put into production by MADE.com.

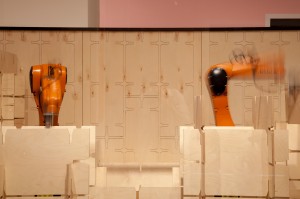

Newson asked the exhibition designers and graphic designers (dRMM Architects and LucienneRoberts+) to reference digital processes within the build, so the design became an exhibit in itself. CNC (computer numerical controlled) routing was used to produce layered cardboard shapes, echoing the additive manufacturing process of 3D Printing. Small-scale exhibits were grouped on these “islands”, with very few under glass, heightening a sense of immediacy and availability. Larger-scale and intereactive exhibits include: functioning robotic arms and digital looms; 1:1 scale models of pre-fabricated buildings; furniture available to sit on, and websites set up to for visitors to become “hackivists”, downloading, appropriating, customising and sharing digital designs online. Super-graphics share stats, while neon-sign slogans and directional devices add an air of commercial atmosphere. In the interview (below), Newson explains the concept of the “Third Industrial Revolution”, and explores some of the implications of these emerging technologies, for designers, consumers, design education and the design profession.

The immediacy of this customisable technology is underlined by the display, which alludes to a designer’s creative workspace. Exhibition Design by dRMM Architects

Information displayed as a super-graphic on the gallery’s end wall. Graphic Design by LucienneRoberts+

Liz Farrelly: How did you start researching this exhibition?

Alex Newson: We spent six months researching, actually talking to people more than researching…

LF: …because so little has been written about this?

AN: Yes, and because it’s happening now; and it takes a year or six months to publish, so by the time you have, it’s out of date anyway.

LF: The exhibition is about digital production, new manufacturing methods and innovative materials; how would you describe the “Third Industrial Revolution”?

AN: We’re saying that digital processes are changing the way objects are made, the type of objects that are made, the way we use them, and the way the public plays a part in production and use.

LF: Like Web 2.0 – accessible content – but for products?

AN: Yes. In Chris Anderson’s book, Makers: The New Industrial Revolution (Random House Business, 2013), which was published around the time we started researching, he refers to this as “bits and bites”. The digital revolution is all about “bites” but the third industrial revolution is all about “bits”; it’s the real things as opposed to the digital things. You can go from digital to physical and back to digital at the drop of a hat, which has been possible for a long time, but now it’s available to everyone, so you can reverse engineer an object — 3D scan it and print it. Those two worlds have now been stitched together and that’s a fundamental change.

LF: How did you choose the projects for the exhibition?

AN: We asked, does this work as an exhibit and fit into the meta-narrative? Curating is quite an organic process.

LF: Was the aim to have projects that were interactive and show off processes?

AN: Exactly; can the viewer “get it”? And is it a fun thing to look at? There are books on the subject, films have been made, but we were producing an exhibition, so it has to be right for the format. We acknowledge that we’re only scratching the surface, so we made a blog and asked other people to tell us what we missed.

LF: In the exhibition there are some working machines. How do the visitors react?

AN: Our “Future Factory” was the most successful part of the exhibition. Visitors said they enjoyed it the most. If we hadn’t included “making” in the exhibition then we would have failed at the first hurdle. These technologies are similar to desk-top-computing, which enables someone working on their own with no previous experience, to write a book, to self-publish, to print on demand and distribute over the Internet. Now these digital manufacturing processes are enabling us to do the same thing with physical “bits”.

LF: Desk-top-publishing had a massive affect on the graphic design industry, and graphic designers had to adapt to survive. How do you see the role of graphic designers in the future, during this third industrial revolution?

AN: It’s tricky because the design disciplines are so different. One of our ideas with the “Future Factory” was to take six of our front-of-house staff who had no experience of digital manufacturing, give them two days of basic training in how not to break the machines — not necessarily in how to use them — and say, make whatever you want. No other brief; just use your creativity and go wild. They are creative people — graphic designers, illustrators, photographers — and they all have knowledge of 2D image making, and use Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop. But for them it was a big leap to make, into three-dimensional modelling, and it demonstrated that there is a different way of conceiving things in two or three dimensions.

LF: So, some disciplines are not yet exploring the possibilities of 3D, nor are colleges teaching it?

AN: But it can happen; you need to be taught it in parallel. You can’t be expected to make that transition from 2D to 3D without actually playing with it.

LF: It’s similar to when computers first appeared in design colleges; there was a time-lag between the new technology becoming available and tutors and students acquiring the necessary skills.

AN: Exactly.

LF: So, the Design Museum staff who were already trained as image-makers and communicators experienced a learning curve?

AN: Quite a steep learning curve; they kept thinking about a three-dimensional object as a series of 2D planes, rather than conceiving it in three-dimensions from the outset. That is the leap to make, and it isn’t impossible to do, or difficult but it is a journey that you have to do, and then all of a sudden you get it and you understand spatial geometry and the interplay of geometry.

LF: Talking about the third industrial revolution, do you perceive that it’s happening mainly in the realm of 3D? Or does some of the technology in the exhibition relate to graphic user interfaces and the 2D world of communication?

AN: I think it’s already happened in 2D, with digital print on demand, for example. Graphic designers have experienced the digital revolution; now it is available to industrial designers.

LF: Similarly the ability to kick-start a project without a client has had a huge impact on graphic design, with designers creating their own content and publishing their own printed media.

AN: Now you can do that with products, and you couldn’t do that until relatively recently. Arduino and Raspberry Pi have enabled the prototyping of electronics. Now you can program something, stick it all on a little board and do-it-yourself. That hadn’t been possible; you would have needed vast resources to do any electronic work.

LF: So, illustrators and graphic designers could be making 3D products?

AN: So could consumers, not just designers! It’s democratisation, enabling anyone to play a role in production.

LF: Some would say there is a downside, in the de-professionalisation of the design process and a knock-on effect for the design industry. Young designers are worrying about what’s happening to their profession.

AN: It was one of the questions I asked the designers in the exhibition; are you worried for your profession? Does this make the designer obsolete? And they all said, no, of course it doesn’t! I think the best illustration of that is Assa Ashuach, who has a project called Digital Forming. He makes what he calls, Original Designed Objects and Co-Designed Objects, or ODOs and CODOs. It’s the idea that he or anyone can design an object on the platform, with certain locked-down points that can’t be changed or customised. And then the consumer goes on to create a co-designed object, around those points that can’t be changed, so the object never loses functionality. Ashuach used the example of a lemon squeezer, because if you let someone customise it as much as they want it could become useless. Instead, you have to retain the designer’s “hand” in the process.

LF: Co-design is an interesting solution.

AN: There were similar concerns around desk-top-computing and the idea that anyone could be a graphic designer; and yes they can, but not everyone can be a good graphic designer, and the good stuff will always float to the surface. Potentially, though, consumers can engage with the process of design and manufacturing more than they have done before, and that can only be a good thing. They can be the designer if they want to be, but they could also just have some input.

LF: And that new level of engagement could lead to a better understanding of the design process in the future.

AN: Perhaps. Unto This Last make furniture in East London using Computer Numerical Control (CNC), a very old digital production method that cuts plywood and has been around since the 1940s. Because they use digital processes you can choose how big you want your table, how tall you want your stool, even if it’s just a relatively small amount of customisation…

LF: …but it can make a big difference when you are investing in a piece of furniture with specific requirements for size or function.

AN: Yes. And because they use digital processes they’re able to make each piece in a day, which means they can be affordable even though it is small batch production. Previously, customised goods were also luxury goods, because they were handmade. Another side of the third industrial revolution is that, potentially, it will disrupt a traditional element of luxury, which will have to change and become something beyond customisation.

Photographs courtesy of Design Museum: nos. 1,2,4,7,8.