This post was originally published on Eye Blog. I’m reposting it because I recently added a separate post about Fiona Raby’s talk at this conference, which provides background to the Dunne & Raby exhibition, “United Micro Kingdoms: A Design Fiction”, reviewed here.

Counterpoint

The 2013 D-Crit Conference, School of Visual Arts, New York City

Attended 11 May 2013

Monday 12:15am, 24 June 2013

“Sharing the stage…sharing ideas”

by Liz Farrelly

Originally published on Eye Blog

Five D-Crit students team up with experts to make presentations at their graduate symposium

It’s that time of year again, when a host of graduating art and design students prepare to launch themselves upon the world. The degree shows have gone up and this year’s crew are buzzing with anticipation. That’s fine if your work looks good on a wall or in a gallery. But what about the new breed of design critics on Masters courses on both sides of the Atlantic? Just how do writers make their mark?

Following a precedent set by the RCA/V&A MA History of Design course back in the 1980s (alumni include Michael Horsham, Claire Catterall, Guy Julier and yours truly), the graduate symposium featuring presentations of boiled-down dissertations, live on stage, is now a regular event on academic calendars. While students may consider this to be a final agonising hurdle, it is a proven means of putting themselves and their projects in front of a diverse but engaged audience of potential employers and commissioners – editors, publishers, academics and broadcasters.

The RCA’s two symposia (last week’s History of Design and next week’s Critical Writing) are being staged during the degree shows. Meanwhile, New York’s D-Crit graduates at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) got in early with a conference in May, the fourth annual outing for this relatively new course.

D-Crit chair and co-founder Alice Twemlow (another RCA alumnus) runs the two-year programme, attracting graduates from diverse academic backgrounds, some already holding multiple degrees. However, the rising cost of education and the uncertain job market may be making the luxury of a two-year commitment difficult to justify: this year only five D-Crit students completed. So for 2013, the symposium format was changed to include invited guests, pairing each student with a specialist.

The range of topics made for a fascinating day, and a rare opportunity to witness the likes of Michael Sorkin, Fiona Raby and Toni Griffin sharing a stage. For the students this increased the networking potential of the event. Presenting in a stunning auditorium, Twemlow spoke of “cultivating a community of criticism”, and thanked an impressive roster of technicians and staff, including a “presentation skills coach”. The gloss was evident in the students’ confident delivery, but less so when put on the spot by New York public radio host, John Hockenberry, who acted as compère. Speaking off the cuff is harder.

The day’s theme of “counter/point” (chosen by the students) was prefaced by a catchy snatch of Mr Scruff’s “Get a Move On”, which samples Moondog’s contrapuntal “Bird’s Lament”.

Paola Antonelli, senior Curator at MoMA, delivered the keynote lecture, saying: “I believe that design is the most important discipline in the world”. Referencing the exhibition “Design and the Elastic Mind”, she added: “Design is not about now but about what should be, could be and would be”. Antonelli educated us with example after example of projects that redefined design, from Enzo Mari to Martino Gamper. In the Q&A Antonelli described the value of criticism from the receiving end, too. “I’ve had to change the curators’ and the public’s understanding of design at MoMA. But I have to remain vulnerable, embrace criticism, but be critical of it, too.”

Conveniently, each student thesis was located within a different design discipline; graphic design (Bryn Smith, invited expert Andrew Blauvelt), product design (Tiffany Lambert, with Fiona Raby), architecture (Matt Shaw, with Mark Foster Gage), urban design (Brigette Brown, with Toni Griffin) and landscape design (Cecilia Fagel, with Michael Sorkin).

Bryn Smith opened by asking whether graphic design can work in a gallery. After showing several graphic design exhibitions, where “one solution doesn’t exist”, her answer was yes. When questioned by Hockenberry, Smith suggested that as the public becomes more visually literate, “we can challenge them”. Andrew Blauvelt commented that as the public use social media to instantly feedback on new logos etc., they will challenge back.

Tiffany Lambert began boldly: “Product design is conducting an experiment…collaboration is the answer but what is the question?” Fiona Raby demonstrated a fantasy future of design describing Dunne & Raby’s new exhibition, “United Micro Kingdoms”, the aim of which is to prompt Design Museum visitors to imagine their own futures. After giving us a history of critical design Lambert said: “participation is as amorphous as democracy”. When questioned by Hockenberry, Lambert replied that voting is only the minimum requirement of democracy, and that the point of speculative design is to challenge the role of designers, users and the system.

Matt Shaw demonstrated the way critical engagements inform his architectural projects, which he locates under the mantle of “Avant-Pop”. When questioned, both Shaw and Mark Foster Gage (clients include Lady Gaga, Diesel and Intel) agreed that they are attempting to engage a broader public with architecture – Gage by way of “effect”, while Shaw is more “literal”.

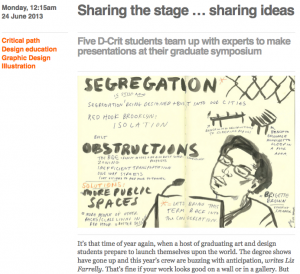

The most impressive pairing of the day was Brigette Brown and Toni Griffin (of the J. Max Bond Center). Griffin introduced the concept of the “Just City”, where equity, diversity and democracy is paired with advocacy. Brown’s pragmatic observation and analysis (of a Brooklyn neighbourhood) showed how small interventions in the materiality of public space and the routing of mass transit might blur the line between gentrification and ghetto and overcome the “segregation that is still being designed and built into our cities”. When questioned, Brown replied with a list of suggestions; take down fences, mingle businesses, make parks for walking (not just bikes and sport), and landscape the [public housing] Projects.

“Make no mistake, the planet is going to hell in a hand basket”, said Michael Sorkin before presented his version of Utopia. By contrast, Cecilia Fagel questioned the way plants are used to “green-wash” public space in Manhattan: “nature is not a pop-up store”. As budgets are cut, planting that could make a real difference in marginal areas loses out to high-profile, controlled planters which are no more than security barriers. When questioned, their opposing stances melded. Fagel: “If the people participate you don’t need top down”. Sorkin: “We’re both talking about equalising access to quality”.

At the start of the day Hockenberry had contemplated the role of the critic; “Design critics need to poke designers in the eye…the communication deficiencies of designers are made up for by design criticism dialogue…People need to understand why stuff is the way it is. Designers are part of that process but only the critic can bridge all the sources.”

Disappointingly, the final debate of the day featured the professional specialists rather than the students, and with Hockenberry’s comments still ringing in my ears, I thought it was a shame that the D-Crit graduates were not able to “work over” their elders. Yet this was a symposium at which students were put on the spot, which meant that we heard a more hesitant voice that differed from the polished presentation performance. The process denoted thinking, but that’s not always comfortable to watch!

Defining design criticism is more problematic. On offer was some design history mixed with some design theory (or design culture, call it what you will). And we need both in our criticism if it is to get beyond an already informed elite and make sense to a wider audience, those wanting to know but who need some things explained (the precedents, the process). If design criticism includes explanation and information along with ideas, opinions and proposals, it will be more than the sum of its parts. If we’re not vigilant about spreading the word, though, all we are doing is preaching to the converted.